"Board-Certified": What Does It Actually Mean?

Inside America’s confusing and sometimes misleading world of medical boards

“Board-certified” is a powerful term for a physician. It is authoritative and conjures up rigorous training, competence, and experience. Yet many people are shocked to learn that in America, there is no national definition of “board certified,” and that not all certifying medical boards are the same. In addition, a doctor does not have to be board-certified to have a license to practice medicine.

Consider this phrasing: “Dr. Smith is an experienced, board-certified physician who has been practicing dermatology for over ten years.” No one could be faulted for assuming Dr. Smith is an experienced, board-certified dermatologist. However, Dr. Smith could be a board-certified internal medicine doctor who went to a couple of weekend courses to learn how to inject Botox. The clinic is so profitable, she is planning on adding hormone pellets after she attends a course.

Fair warning, this is more of a book chapter than a Substack post. Absurdly, there is really no way to make it shorter. I flirted with making it a drinking game: Take a shot every time you read ABMS (don’t worry, you’ll get it soon enough!). But I decided against it as I don’t want people to get alcohol poisoning, and for those who don’t drink alcohol, I don’t want any burst bladders. You can head to the “In Summary” heading at the end if you are pressed for time, but honestly, you really need to read it all. I am in full Alice mode and am waaaaay down the rabbit hole.

American Board of Medical Specialties or ABMS

In the United States, the term board-certified most often applies to a medical doctor or osteopathic doctor who has completed the requirements for one of the 24 certifying medical boards of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS, which I will put in bold as it is the gold standard and there is another board with a very similar name and when we get to that part you will never be able to keep them apart otherwise). There are also medical boards for osteopathic doctors (DOs), which I will not review, as I am not familiar with them, though I assume the structure is similar. DOs can cross over and complete ABMS boards. I know many excellent DOs, and will tolerate no DO slander.

Think of different boards of the ABMS as different faculties at a university. Just like a university has a faculty of arts and engineering, there are medical boards for each of the major, recognized medical specialities or branches of medicine, such as OB/GYN, Internal Medicine, Urology, Emergency Medicine, and so on. You can find a list of the 24 boards here.

The individual ABMS boards set standards for acceptance and ongoing evaluation of competence. To become board-certified, a medical student must graduate from an accredited medical school, complete an accredited residency, and then pass the licensing exams. In surgical fields, preparing a list of surgical cases is generally also required to demonstrate a surgeon has performed enough of the required procedures to be competent. There are also subspecialty boards, which we will get to below.

Medical boards should not be confused with government agencies that issue medical licenses, generally referred to as State Medical Boards, but the names can vary by state, adding to the confusion. (Sigh). Here are some examples (full list is here):

Alaska State Medical Board

Medical Board of California

Connecticut Medical Examining Board

Florida Board of Medicine

State Medical Boards grant licenses to practice medicine, enforce standards, and take action on complaints about patient safety or unethical behavior. A doctor DOES NOT have to be board-certified in a medical specialty or even complete a residency to have a medical license. To get a license to practice medicine in the United States, a doctor must attend an accredited medical school, complete one year of an approved residency, and pass an exam called the USMLE Step 3 (which is usually taken in the first year of residency). Dr. Peter Attia cannot be board-certified by any ABMS board as he did not complete residency, but he meets the lower bar to get a medical license.

Why Be Board Certified by an ABMS Board?

Maintaining board certification in an ABMS board demonstrates basic competence and a commitment to staying current in the field of practice to peers and patients. Also, when a doctor is board-certified by an ABMS board, a patient knows that their doctor has completed an accredited residency.

The other reason, from the physician’s perspective, is to maximize employment opportunities. Some hospitals require ABMS for hospital privileges, and some medical groups require it to become a partner. Many insurance carriers also require ABMS for a doctor to be included in the network, and it may matter to a malpractice carrier. Being board-certified is not a requirement to bill Medicaid or Medicare. Someone who plans to open a concierge practice and never bill insurance or work in a hospital does not need to be board-certified.

You can see if your own doctor is board-certified by ABMS by clicking this link.

Aside from some unique concierge business models, why else might a doctor not get board-certified after graduating from an accredited residency?

Difficulty passing exams.

Family circumstances that come up (sometimes exceptions can be made).

Doesn’t want to “play the game” or pay the money. Senator Rand Paul, an ophthalmologist, founded his own ophthalmology board, the National Board of Ophthalmology.

Cost. Some doctors leave residency with significant debt. In some cases, it’s not just the cost of the exam itself. For example, the OB/GYN oral exam must be taken in Texas, but for most people, that means airfare and a hotel. It may also mean arranging babysitting.

Personal safety. This is relatively new and uniquely American. For OB/GYN, the oral exam happens in Texas, which means traveling to a state where abortion is criminalized. What if a candidate were pregnant and had a pregnancy complication that could not be managed appropriately in Texas because of the laws? You might understand how someone who is 19 weeks pregnant may not feel comfortable traveling to Texas for an exam.

General annoyance/anger with the concept of medical specialty boards, as they rarely do anything to curtail bad behavior. For example, there are OB/GYNs who lie about abortion, but lying to patients doesn’t seem to be worthy of censure. And then there are those who spread all kinds of disinformation, like Dr. Christiane Northrup, and despite petitions from OB/GYNs (led by the amazing Dr. Jennifer Lincoln), nothing has been done to de-certify her. Northrup is an embarrassment to the profession, and she lowers the value of board certification. I understand this annoyance, but instead of giving up on a bare minimum of competence, we should work to create better rules to protect the public.

Does not have the surgical case load to meet the surgical requirements for the surgical boards.

Is super into pseudoscience and wants to not be associated with the ABMS and instead be a member of a non-accredited board that promotes money-making ventures like ozone therapy and unnecessary hormone testing.

Recertification for ABMS Certification

What a physician learns in residency will almost certainly change with research, and of course, knowledge erodes over time, so proof of ongoing competency is needed. (Doctors who became board-certified before a certain date were sometimes grandfathered in and can avoid re-credentialing, but that ended decades ago).

Recertification by ABMS is usually called maintenance of certification or MOC. These programs vary in design (exams every 5-10 years or an annual knowledge assessment from reading curated articles and answering questions), and they are associated with modest improvements in physician knowledge, adherence to evidence-based care processes, and patient outcomes, including reduced mortality. There are legitimate questions about the optimal design and implementation of MOC programs, and I know that some doctors are strongly opposed to MOCs, but I just don’t get it. We can absolutely disagree and discuss the best path for continuing education, but physician knowledge and skills do decline after residency. One study tracked general practitioners from medical school through more than 20 years of practice and found that, while knowledge reached peak levels among physicians certified less than 10 years before, knowledge decreased from 10 years after certification onward. Knowing that, it’s hard to argue against some type of standardized ongoing maintenance of certification.

Some doctors let their board certification(s) lapse. A doctor who goes into a different career might do this, and no one would bat an eye. But there is also a specific type of concierge medicine where a doctor has become so huge a business that board certification is irrelevant, or the doctor views the evidence-based practices supported by the ABMS as beneath them, cumbersome, woke, or bad for business. While I can’t guess why he made this decision, Dr. Mark Hyman is no longer board-certified by an ABMS board; he is now affiliated with a non-ABMS organization, the Institute of Functional Medicine.

Subspecialty Certification

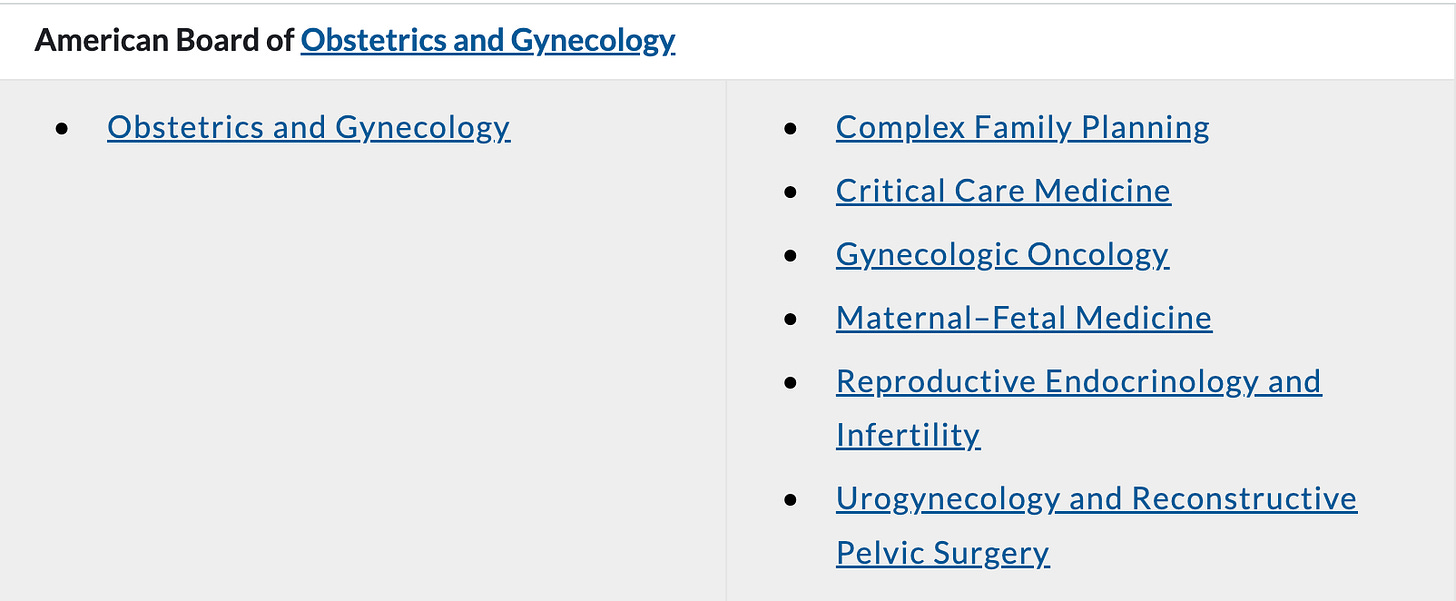

Within medical specialities, there are subspecialties. You can find the list of ABMS-recognized subspecialties here. For example, OB/GYN currently has six:

An ABMS-recognized subspecialty requires a fellowship (more specialized training), often with a research component, and an exam. As some subspecialties are new, there may be people who were grandfathered in who did not do a fellowship but did an exam. That is how I obtained my pain medicine subspecialty board certification through the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (ABPMR) in 2002; soon after I passed the exam, a fellowship was required.

Many boards consider subspecialty certifications an extension of the primary ABMS certification, so in these cases, a doctor can maintain their subspecialty board certification only if they maintain their general ABMS (the parent board certification, if you will). But that is not always the case. It’s not uncommon for people with subspecialty boards to drop their original board certification when allowed, or to give up a speciality certification if their practice changes, because maintaining multiple board certifications can be expensive and time-consuming. For example, I let my ABPMR pain subspecialty board certification lapse after 20 years because the pain medicine aspect of my practice is winding down.

The key here is whether a doctor has a speciality or subspecialty certification from the ABMS; if so, the doctor should be current with all requirements. When you search for a doctor on the ABMS website, it returns results from both general and subspecialty boards.

Non-ABMS Boards

There are many medical boards that exist outside of the rigor of the ABMS ecosystem, with a wide range in quality. It’s really a boards-a-palooza. I’d laugh at the number (and in no way can I cover them all), but the consumer suffers because how are they to know which board certification process is truly rigorous and which is more closely related to multi-level marketing? I could start a “Medical Board of Holistic Gynecology,” and as long as I didn’t claim it was related to an ABMS board (more on that in a minute), that would be fine.

Some of these non-ABMS boards are subspecialties that have a well-defined scope of practice that require specialized knowledge beyond residency, have a demonstrable body of scientific literature, and are recognized by the broader medical community, but haven’t quite yet reached the threshold of being accepted by the ABMS (it’s a lot of work to get a a speciality or subspecialty recognized, demonstrating the high level of rigor involved). There are also medical boards that appear to me to exist primarily for marketing and/or credential inflation.

And while I can joke about my Board of Holistic Gynecology or Dr. Rand Paul setting up the National Board of Ophthalmology to avoid the woke mind virus, how is the public to know that either of these medical boards is a joke? (mine a joke-joke, and his, a joke come to life). This is, unfortunately, why lay people can’t just take “board-certified” at face value. The freedom to create medical boards to offer the illusion of competence feels sadly American to me.

Here are a few types of non-ABMS Boards:

Non-ABMS Subspecialties

There is a wide range here. For example, the American Board of Pain Medicine and the American Board of Obesity Medicine are generally considered legitimate non-ABMS boards. These are recognized fields of study, and applicants must be members of an ABMS board to apply, indicating a minimum standard of accepted competency for these qualifications. Often, these boards are relatively new fields, and some may be on the pathway to acceptance by the ABMS. A good rule of thumb is to check whether the non-ABMS board requires ABMS certification in another specialty. If they do, it’s generally a higher standard.

In comparison, the American Board of Anti-Aging Medicine (ABAAM) website feels to me like a sales and marketing program (they even have a corporate tier, which appears to be a way to pay more to get more referrals), and they advertise that a reason to get certified is to earn more money. Most physicians don’t consider anti-aging medicine a legitimate field, and I could find no requirement for ABMS certification; in fact, they accept chiropractors. Also, you have to pay to attend two of their sponsored courses to take their exams. I would not personally consider this a legitimate medical board.

In plastic surgery, there are at least three non-ABMS subspecialty boards. A 2024 study in Annals of Plastic Surgery compared the American Board of Plastic Surgery (which is ABMS) with the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery (ABCS), American Board of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (ABFPRS), and American Board of Facial Cosmetic Surgery (ABFCS). I know, hard to keep straight, right? They concluded that the American Board of Plastic Surgery (an ABMS member board) “stands apart as the only board within the aesthetic marketplace with rigorous standards for pre-certification training, demonstrating competency through examinations and case logs, and maintaining certification.” California, which restricts which medical boards can be associated with the title “board-certified,” accepts the American Board of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (ABFPRS) as a non-ABMS board of appropriate rigor to use the title “board-certified.” The American Board of Cosmetic Surgery accepts non-plastic surgeons, such as OB/GYNs, thoracic surgeons, urologists, orthopedic surgeons, general surgeons, and dermatologists who then complete a one-year cosmetic surgery fellowship training (the dermatologists can only be certified to operate on the face), and this board does not meet the standards for board certification in California. So you know, it requires six years of plastic surgery training to become an ABMS-certified plastic surgeon.

The American Board of Physician Specialties

Also known as the ABPS, hence you now understand my use of bold for ABMS.

This is an alternative board to the American Board of Medical Specialties, with fewer specialties and subspecialties. However, ABPS has some subspecialties that are not included in the ABMS. Not every institution or state licensing board considers ABPS certification as meeting “board-certified” requirements.

Like ABMS, ABPS requires training, exams, and recertification. The ABPS accepts a broader range of foreign or international residencies than the ABMS boards, and some of the specialties have an experience pathway (where experience can replace some training), which I believe has been phased out with ABMS boards. I couldn’t find any papers comparing patient outcomes or skill levels between ABMS and ABPS board certification, so I looked at the two boards I am familiar with, OB/GYN and pain medicine, to identify differences. To me, the requirements for the ABMS board certification and maintenance of certification for OB/GYN are more rigorous than ABPS. For example, OB/GYN does not require an oral exam for AMPS, but it is required for AMBS, and the AMBS recertification is more structured, with more defined educational goals. For pain anesthesia, a fellowship is required for ABMS certification, but there is an experience pathway for AMPS certification. I couldn’t find detailed information on recertification for ABPS pain medicine, but it was easy to find for ABMS.

I read some information on the ABPS website (from late 2025, so recent) and learned that they claim that the maintenance of certification (known as MOCS and how we prove our competency) for the ABMS is “burdensome,” and that “doctors already have market incentives to continue their training and education, as it pertains to their practice rather than squeeze into one size fits all requirements.” We have data suggesting that isn’t the case. The ABPS also complained about the high cost “to remain board certified.”

I get that maintaining multiple board certifications incurs some cost. I have maintained my Canadian equivalent (Royal College certification) since 1995 (which gets me nothing financially here in the United States, but it is a massive source of pride), my OB/GYN ABMS boards since 1997, and my two pain medicine boards from 2002/3 ish to 2025. I’ve paid a lot in dues and recertifications, so I don’t have much sympathy for a physician complaining about the cost of maintaining one. The cost to maintain my OB/GYN ABMS boards is about $290 a year and is less than my medical license in California. It’s also less than the $895 per year most teachers spend on classroom supplies, according to a 2025 survey performed by adoptaclassroom.org, just to keep this in perspective.

For comparison, the cost of ongoing certification with the ABPS for OB/GYN is $200 every two years (if I read it correctly, it was a little confusing), plus an exam fee at year eight. The ABPS OB/GYN ongoing recertification requires completing continuing medical education credits and answering questions and it is up to the physician to assemble those. The links they provide lead mostly to paid content. I clicked their first link, and the cost to get the CME credits was $399. I’m not arguing about a CME site charging for their product, but don’t use the cost of continuing education as an argument for your medical board, and then when I click the link to the recommended CME, I have to spend more and the cost savings evaporate. Also, the CME did not impress me compared with what I have done via my ABMS board. The CME articles for the ABMS OB/GYN boards are part of the $290.

I have one red flag from the ABPS website: content promoting a 30-day plan for balancing hormones. I am not surprised, as they offer board certification in integrative medicine. Many experts worry that much of the “integrative medicine” research is less reliable than it appears. Studies tend to be small, poorly controlled, or don’t measure outcomes that actually matter (like reduced risk of cancer, control of blood pressure, or reduced risk of diabetes). Instead, they often focus on surrogate markers or biological theories that sound convincing but don’t prove real benefit. There is also frequent cherry-picking of positive studies, financial ties to supplement or testing companies, and a tendency to market treatments widely before there is solid evidence. This doesn’t mean everything labeled “integrative” is useless; things like sleep, exercise, good nutrition, stress management, and some mind-body therapies are well supported (and I would just call medical care), but given the reliance on weak or selective evidence, it’s not surprising that integrative medicine has not found it’s way into the ABMS system.

The Language of Board Certification

There are a lot of different board certifications, and when a doctor says they are board-certified, how do you know what that means? The answer: you don’t, as it varies state to state. The best practice is for doctors to be specific, for example, I would say that I am board certified in Obstetrics and Gynecology by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

There are about 70 state licensing boards (some states have separate licensing boards for medical and osteopathic doctors, while others combine them). According to Wikipedia (I am sorry, I just can’t look them all up), about 20 states do not consider ABPS equivalent to ABMS for the definition of board certification. How the state licensing boards approach the language varies. For example:

In Texas, special approval is required to claim board certification that is not from the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), the American Osteopathic Association Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists (BOS), or the American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (ABOMS).

In Florida, board-certification applies to both ABMS and AMPS. Other boards can petition to be accepted. However, a physician can advertise a non-recognized board if the advertising says “The specialty recognition identified herein has been received from a private organization not affiliated with or recognized by the Florida Board of Medicine” and it is in the same size print as their name.

In California, a doctor can only claim they are board-certified if they are certified by the American Board of Medical Specialties or one of these non-ABMS boards: American Board of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, American Board of Pain Medicine, American Board of Sleep Medicine, American Board of Spine Surgery. I looked up some doctors with cosmetic surgery centers in California who have American Board of Cosmetic Surgery qualifications (not allowed to claim board certification in California), and who do not have any of the above boards and who did not train as plastic surgeons. They seem to be following the regulations by using terms like “leading cosmetic surgeon” or “highly experienced cosmetic surgeon.” I suspect many in the general public would falsely assume that doctor completed a plastic surgery residency and is board certified by ABMS.

Many states don’t specifically spell out the definition of board-certified, but are clear that doctors should not misrepresent themselves or they could face disciplinary action. Definitions of “misleading” will likely vary by board, who is making the complaint, and if a patient had a complication because they assumed the physician had more training based on the advertising. It seems fine in many states to say something like “board-certified by the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery, with extensive training and experience in Orthopedic Surgery.” It may or may not matter to you whether the person performing your facelift or liposuction trained as a plastic surgeon or as an orthopedic surgeon, an oral surgeon, or an OB/GYN. As long as the medical board is spelled out, it’s probably legal in most places, so it’s up to you, the consumer, to know what that means if it matters to you.

In Summary

There are a ton of medical boards, some more legitimate than others. It’s a bit of a sliding scale in terms of the quality of training and the demonstration of the minimum level of competence, and then maintaining that competence. This is a huge issue because the average consumer likely believes that board certification always means highly qualified, but that may not be the case.

Here is my best stab at a summary:

If your doctor has not posted about their board certifications, there is a good chance they are not board-certified by the ABMS. Pay attention to the language, and when they use words like expert, did extensive training, leading, etc., and they don’t mention board certification, that is a red flag to dig deeper, if this matters to you. Cosmetic procedures and hormone-related issues (including menopause) are likely the biggest areas where you may find doctors working outside of the scope of their training.

When a doctor mentions they are board certified, they should be specific and say what board.

Medical licensing boards are not checking websites. If you feel you have been misled, the best recourse is to complain to the state licensing board.

The American Board of Medical Specialties is the gold standard for specialties and subspecialties. You can look up whether your doctor is board-certified by an ABMS specialty or subspecialty here. No registration is required. If your doctor is listed, you know they have done an approved residency. However, that residency MAY NOT be in what they are advertising. For example, you might care that the person performing your facelift or liposuction trained as an OB/GYN or oral surgeon. Or that the person offering you Botox is board-certified…in radiology. I would!

There is no data comparing doctors qualified by ABMS vs. ABPS. ABMS is considered the gold standard, and based on my reading, I agree, but, I am sure there are also many excellent ABPS doctors. My caveat is that I find it highly problematic that a board of medical specialties, an organization that sets medical standards, is promoting a 30-day plan to balance hormones from one of their members. It makes me wonder if any non-evidence based integrative medicine creep could be happening in their other specialties? To check whether your doctor is certified by an ABPS board, click here.

ABMS or ABPS board certification does not mean a doctor is good, just that they have completed specific training and demonstrated a basic level of competence.

There are many non-ABMS boards for subspecialties, some far more valid in my opinion than others. Sorting the wheat from the chaff here is not easy for people outside of the system. California recognizes these four non-ABMS boards as worthy of the term board certification:

American Board of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

American Board of Pain Medicine

American Board of Sleep Medicine

American Board of Spine Surgery

What I really need is money from some philanthropist, like Mackenzie Scott, to hire some smart people to look at all the medical boards, the requirements, the recertifications, and then come up with a free website and app where people can find out what it all means and check up on their doctor. And this is needed, because in America, the ability to start a medical board doesn’t have to be tied to a new, legitimate field of study that is slowly being recognized and working towards ABMS certification, it can also be the product of a growing market that can be best capitalized on by credential inflation.

It’s patient beware, and hopefully this information here will help.

References

van Leeuwen YD, Mol SS, Pollemans MC, Drop MJ, Grol R, van der Vleuten CP. Change in knowledge of general practitioners during their professional careers. Fam Pract. 1995 Sep;12(3):313-7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.3.313. PMID: 8536837.

Chen S, Lineaweaver WC. Evaluating Board Certification Within the Aesthetic Marketplace. Ann Plast Surg. 2024 Sep 1;93(3S Suppl 2):S119-S122. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000004056. PMID: 39230296.

Long EA, Gabrick K, Janis JE, Perdikis G, Drolet BC. Board Certification in Cosmetic Surgery: An Evaluation of Training Backgrounds and Scope of Practice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020 Nov;146(5):1017-1023. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007242. PMID: 33136946.

Thank you for making these important distinctions and understand the nuances to help people become an informed consumer/patient.

You were not kidding that this was a deep dive:) I am a ABOG certified obgyn and learned a lot! My question is how do we educate people being bamboozled by "functional medicine menopause experts?" It makes me sad especially when physicians (that are usually not gynecologists) are doing Dutch tests ordering expensive compounded hormones having pts come back every 3 months for "levels" and people think they are getting superior care. Ok, maybe it actually makes me angry.... Thanks for what you do. I really enjoy your writing