Fibroid Research in Fallout from Trump's Cuts

We are looking at generational harm to medical care

The Trump administration has been busy gutting scientific programs right and left, and the result will be generational harm. There is no other way to describe it. Each time I see a program or grant cut or threatened, I can envision so many pathways for harm. It’s like a malignant version of the butterfly effect.

For example, one grant studying an mRNA vaccine for COVID has been terminated, and scientists have been told that they need to remove all references to mRNA vaccines in their grants. This is a tragedy as mRNA vaccines hold great promise for many conditions. In fact, an early phase clinical trial with an mRNA vaccine for pancreatic cancer has had impressive results. Pancreatic cancer is an especially deadly cancer, so here we are, potentially on the cusp of a breakthrough that may now never happen. Research on obsessive compulsive disorder, a herpes vaccine to reduce complications in the eye from infection, lipid metabolism, prenatal exposure to phthalates…the list of affected grants goes on (you can find a list here).

Many of the cancelled grants come from or through Columbia University and are a fall out of the $400 million in federal money that Trump is withholding from Columbia, claiming it is punishment for antisemitism on campus. Although now Columbia may be caving to Trump, and in the process give up some academic freedom (you can read more about the back and forth here). Coincidentally, according to the New York Times, $400 million is the amount of money Trump wanted Columbia to pay him 25 years ago for a real estate deal that never happened because Trump was apparently mercurial and difficult to deal with and wanted a lot more money than the land was worth (it was appraised for $65 million to $90 million), and so the deal never went forward.

When word of these cancelled grants from Columbia hit the news, many researchers took to social media to voice their despair. And among those was Daniella Fodera, a PhD student at Columbia, whose research on fibroids was funded via the NIH.

Among the hundreds of millions of dollars of lost funding, this loss really stuck out for me because we really are in our infancy of understanding fibroids. Every research dollar is so precious here. I reached out to Ms. Fodera to ask her more about her fellowship and what she is studying, because I think spotlighting an individual grant or, rather, loss of a grant, can help us see what we all stand to lose considering women’s health, and especially reproductive health, is so underfunded to begin with. And while her grant is relatively small compared to numerous other studies, it’s these projects that plant the seeds. If we can’t understand the basics, it’s a lot harder to design therapies and prevention.

First, Some Background on Fibroids

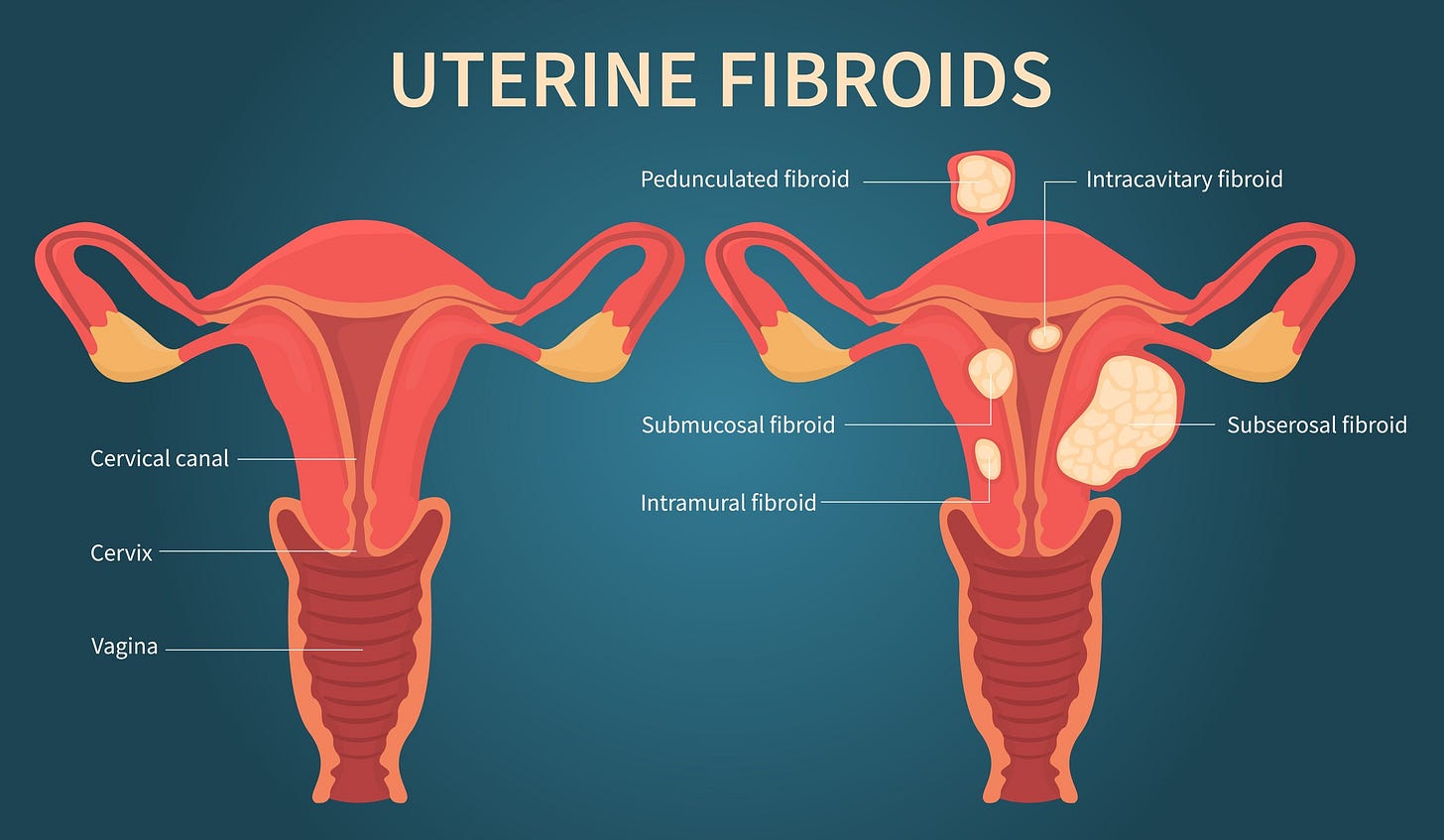

Fibroids are benign or non-cancerous tumors of myometrium (the muscle of the uterus) and they are known medically as leiomyomas. They can range in size from a seed to the size of a volleyball, and people can have one or they can have multiple. Fibroids can cause heavy bleeding and sometimes bleeding between periods, menstrual cramps, and when they are large, they can cause a pressure sensation and can even contribute to incontinence. Some fibroids can affect fertility and, if a fibroid outgrows its blood supply, it can be very painful.

Fibroids are a bit of a conundrum, because between 50-75% of them just hang out in the uterus minding their own business, causing no symptoms. Why are some so problematic and others just along for the ride? We don’t know or at least don’t fully understand, which is one reason why we need to study them.

Fibroids are common — by 50 years of age 70% of White women and over 80% of Black women will have at least one fibroid. Black women are more likely to develop fibroids earlier in life, have multiple fibroids, and endure more severe symptoms.

The belief is that fibroids are the result of a dysregulated stem cell, meaning the cell gets an abnormal signal to divide and grow. There probably isn’t a single trigger, rather it’s a combination of factors, such as genetics, hormones, childbirth, and environmental exposures. One important thing people should know is people with fibroids are more likely to have high blood pressure, and the hypothesis is that both fibroids and high blood pressure involve abnormal signaling in smooth muscle, so it’s important that someone with fibroids also have their blood pressure checked (and followed regularly), and of course treated if indicated.

How fibroids cause abnormal uterine bleeding is not completely understood and there are likely multiple reasons. Fibroids affect the chemical soup in the uterus, for lack of a better term, meaning the affect various growth factors, hormones, and inflammation that are key in triggering menstruation, repairing the lining of the uterus after menstruation, and governing the behavior of blood vessels. A local chemical trigger like this would explain why smaller fibroids can cause devastating bleeding. Fibroids may also affect blood flow to the uterus and the physical presence of a fibroid may distort the endometrium and/or affect how the uterus contracts during menstruation. While predicting whether an individual fibroid is the cause of bleeding is hard, those that distort and grow into the endometrium (submucosal and intracavitary) and those that are located primarily in the myometrium (myometrial) are far more likely to cause bleeding issues than those located on the outside of the uterus (subserosal and pedunculated).

There is a lot we don’t know, and currently most of our therapies revolve around manipulating reproductive hormones, procedures to reduce blood flow to fibroids, or surgery to remove the fibroids or the uterus. I believe we could do better, but we need to understand the basics first to get there, which is why research like Ms. Fodera’s is so important.

Ms. Fodera was gracious enough to tell me about her project and where things stand for now via email (there is good news), and I think you’ll find it as interesting as I did.

Can you tell me about your fellowship? I understand you were to study the biomechanics and mechanobiology of human uterine fibroids, but I'd love to learn more.

Of course! This is a prestigious NIH-funded fellowship designed to support promising doctoral students in becoming independent research scientists. My specific fellowship supports my research as a Biomedical Engineering PhD student investigating the biomechanics and mechanobiology of human uterine fibroids.

Uterine fibroids are noncancerous tumors that form spontaneously in the uterus, affecting nearly 70 – 80% of women in their lifetimes. 10-40% of these women will experience clinically significant symptoms, which include severe pelvic pain, abnormal or heavy menstrual bleeding, and infertility. Despite their widespread impact, we still do not know why fibroids develop, and as such, we do not have effective treatment options to prevent or slow their growth. Total removal of the uterus (i.e., a hysterectomy) is the only definitive treatment option for this disease. The research I do seeks to add to our fundamental knowledge of the disease so that better treatments and diagnostic imaging tools can be developed.

Specifically, I am interested in understanding the role of mechanical forces in the development of human uterine fibroids. A key hallmark of uterine fibroids is their increased stiffness compared to normal uterine tissue. My research takes a multiscale approach, examining fibroids at both the tissue and cell length scales, with engineering tools. At the tissue scale, I am mapping the mechanical properties of fibroids of different sizes, evaluating how this may impact the surrounding tissue and how this may change with the menstrual cycle, number of pregnancies, and age. With a cellular approach, I am interested in understanding how stiffness affects the behavior of both ‘normal’ and fibroid cells and how this ultimately drives disease progression.

Is your work about the forces that trigger the development of fibroids or more about understanding the behavior of existing fibroids?

Great question, I would say both!

On the tissue level, I am taking a snapshot of fibroids of different sizes. The normal uterus is about the size of a human fist, but fibroids themselves can range dramatically from as small as a single M&M to as large as an orange or a cantaloupe. For these different fibroids, I am mapping the mechanical properties spatially across their surface. In this way, we can study whether the mechanical properties of fibroids change as they grow and how these growth patterns may occur.

On a cellular level, I am trying to understand how stiffness alone can alter the behavior of normal uterine cells and trigger their conversion into fibrotic ones. Additionally, we are able to study, at a molecular level, the specific proteins that alter the behavior of normal and fibroid cells as a product of stiffness. In doing so, future therapies targeting these proteins could be developed.

In this way, my research evaluates the existing behavior of fibroids and how they may develop so that we can ultimately predict how certain fibroids may act and contribute to patient symptoms.

Had you started your fellowship when you heard about the decision?

Yes, I started my fellowship at the beginning of last semester in September 2024 and was currently in my first year of funding. The process to apply for this fellowship, as with many other NIH grants, is a long and rigorous process requiring multiple independent scientific reviews. I initially applied for this fellowship in April 2023, received a fundable score in August 2023, and then waited an entire year before the NICHD (National Institute of Child Health and Development) decided to fund my research.

How did you end up studying the uterus and fibroids more specifically?

Actually, it was by accident that I started studying fibroids! Prior to this, my research was primarily focused on understanding how the mechanical properties of the uterus change in pregnancy. As I was dissecting uterine tissues for my first study, I started finding these small, stiff, white nodules, think the size of an M&M or smaller, embedded in what appeared to be healthy tissue. The sheer number of fibroids I found shocked me and made me interested in learning more about the disease.

What's next? If you don't know, I completely understand.

For me, my next steps have not changed, thanks entirely to the unwavering support of my advisor and a generous gift from an anonymous donor, I am committed to continuing this work that I am so passionate about as I had originally planned, and I will be defending my thesis in approximately 6 months. Beyond that, it is my ultimate goal to become a research professor in academia so that I can continue studying women’s reproductive health from an engineering perspective. To get there, I must first complete an additional 3-4 years of post-doctoral research training after obtaining my PhD. I am actively applying for post-doctoral fellowships; however, given the uncertainty in the state of scientific research in the US due to recent funding cuts, I am also strongly considering positions abroad.

And anything else you think might be important?

The impact of these scientific funding cuts will be immense, creating generational harm for both scientists and the public at large.

The treatment options for uterine fibroids have remained largely unchanged for both mothers and daughters, even though more than 30 years may have passed between their experiences. This stagnation in innovation is largely due to the systemic underfunding of women’s health research. Recent federal funding cuts will only serve to further delay advancements in scientific research and impede innovation for women's reproductive health.

As a young scientist myself, it is disheartening to see the government divesting from scientific research at large, and it is a move that I believe to be short-sighted. The effects of these funding cuts will be disproportionately felt by young trainees in the early stages of their careers who aspire to continue impactful research that can benefit all of humanity.

My son is also on year 4 of his PhD in MCD Bio and received an NIH grant to fund his research for 3 years in October 2024. All of that evaporated after the inauguration. His research explores the mechanism by which pregnancy decreases breast cancer risk. His research has been sacked because of the forbidden words “female” and “pregnant”. So much important research halted and so many individuals’ lives upended.

This maladministration sucks. They don’t care about anything but hoarding power and money for themselves.