Fibroids 101

The basics for perimenopause and beyond

Fibroids, also known as leiomyomas, are benign or non-cancerous tumors of the myometrium, which is the muscle of the uterus. They are extremely common — by 50 years of age, 70% of White women and over 80% of Black women will have at least one fibroid. About 30% of new fibroids will be diagnosed between the ages of 45 and 49, so many women will encounter this diagnosis during their menopause transition, aka perimenopause.

Fibroids can range in size from a seed to a soccer ball, and people can have one fibroid or they can have multiple. They can also range in impact–about 50-75% of fibroids are just quietly hanging out, not causing any issues, but others can cause a variety of different symptoms or health complications. The most common fibroid-related issue in perimenopause is heavy bleeding, which can also lead to iron deficiency and anemia (iron deficiency can cause brain fog and hair loss, so this is an important consideration for anyone with those symptoms). Heavy bleeding is already more common during perimenopause, so if this happens, it’s important to be evaluated for fibroids to determine if the bleeding is regular perimenopause mayhem or fibroids (and, of course, it can be both).

Other symptoms or health consequences of fibroids include pelvic pressure and pain, typically due to pressure from larger fibroids, and incontinence, due to pressure from fibroids on the bladder. For those who may be planning a pregnancy, fibroids can impact fertility and also cause preterm labor and delivery.

The size of a fibroid doesn’t necessarily correlate with symptoms. Some people can have terrible bleeding from small fibroids, and others can have quite large fibroids and be unaware they even have fibroids. This means it can sometimes take some medical detective work to determine how fibroids are involved in symptoms. Unfortunately, and inexcusably, due to sexism, menstruation-related shame, and lack of access to qualified healthcare professionals, it can often take years and multiple visits to get a diagnosis and understand how fibroids are impacting health.

Fibroids don’t transform into cancer. However, there is a rare cancer that looks like a fibroid called leiomyosarcoma, but the odds of this are less than 1 in 10,000. In general, the risk is higher after menopause, especially when there is a single fibroid that is growing or there is also pain.

What Causes Fibroids?

This isn’t a million-dollar question; it’s literally a multi-billion-dollar question, considering that in the United States alone, fibroids are estimated to cost between $6 billion and $34 billion a year.

The prevailing hypothesis is that fibroids come from a stem cell in the myometrium that gets triggered to divide…and then keeps dividing uncontrollably. (Stem cells are unique cells that can turn into many kinds of other cells and are an essential part of the body’s repair mechanisms). Consider pregnancy. Not only must the uterus make new muscle cells so it can grow, but it must also be able to repair itself after being invaded by the placenta, so stem cells are vital to handle this amount of stress and injury. Fibroids appear to result from a corruption of this normal stem cell growth and repair process.

Both estrogen and progesterone are critical for stimulating the growth of fibroids, which is why fibroids are not seen before puberty and typically shrink, or at least stop growing, in menopause. This may also be why fibroids are more common for people who go through puberty earlier, which means a more prolonged lifetime exposure to estrogen and progesterone.

The effect of estrogens and progesterone on fibroid growth is believed to be due to various reasons, such as regulation of growth factors and inflammation. Estrogen also triggers the development of progesterone receptors in the fibroids, increasing their ability to be stimulated by progesterone. Genetics are likely important in some instances, explaining why some people with fibroids have a family history of them. However, specific genes that we can test have not yet been identified. It’s also possible that some people have genetic variations in hormone metabolism; for example, higher levels of aromatase, an enzyme essential for producing estrogen, have been identified in some fibroids.

Race is an additional risk factor, as fibroids are known to be more common among Black women, although the reasons aren’t fully known. Some hypotheses include higher rates of vitamin D deficiency, as vitamin D deficiency is associated with a greater risk of fibroids. Another cause may be structural racism, which can lead to greater exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (also linked with fibroids) and chronic stress. It is also possible there may be an increased prevalence of genetic variations that impact estrogen metabolism; for example, one study identified higher levels of aromatase (the enzyme that produces estrogen) in fibroids from Black women versus White and Asian women. Asian women also have an increased risk of fibroids, although not quite as high as Black women.

The reason that lower levels of vitamin D are linked with a greater risk of fibroids isn’t known, and there isn’t definitive evidence that supplementation will help. The risk of taking 1,000 IU of vitamin D a day is low, so that may be an acceptable option for people concerned about fibroids or who are at higher risk, although more data is needed. High levels of vitamin E are linked with an increased risk of fibroids, but whether this is cause and effect or correlation is unknown.

Fibroids are more common as we age, so they are lower down on the list of possible causes of symptoms when someone is 20 years old versus higher up for someone age 40. However, it’s also important to know that Black women are more likely to develop fibroids earlier in life, have multiple fibroids, and endure more severe symptoms.

There is growing evidence that people with fibroids are more likely to have high blood pressure, and one hypothesis is that both fibroids and high blood pressure involve abnormal signaling in smooth muscle, as blood vessels also have smooth muscle. For this reason, it’s important that someone with fibroids also have their blood pressure checked (and followed regularly) and, of course, treated if indicated.

Obesity is also a risk factor for fibroids, and the exact reason isn’t known. This may be because of increased exposure to estrogens from fatty tissue and/or increased inflammation.

Interestingly, fibroids are less common among people who have given birth, and the more pregnancies, the lower the risk. After pregnancy, most of the new muscle cells that are created must be removed; otherwise, each pregnancy would lead to a significantly larger uterus. It is hypothesized that during delivery or shortly after, potential fibroid seedlings may be jettisoned along with some muscle tissue. It’s also possible that this may not be a cause and effect, as fibroids can increase the risk of miscarriage, so there may be selection bias here, as women who have multiple pregnancies that go to term are also less likely to have fibroids to begin with.

Starting the birth control pill before the age of 16 appears to increase the risk of fibroids slightly, but not for those who are older, and the injectable contraceptive Depo-Provera lowers the risk.

Location, Location, Location

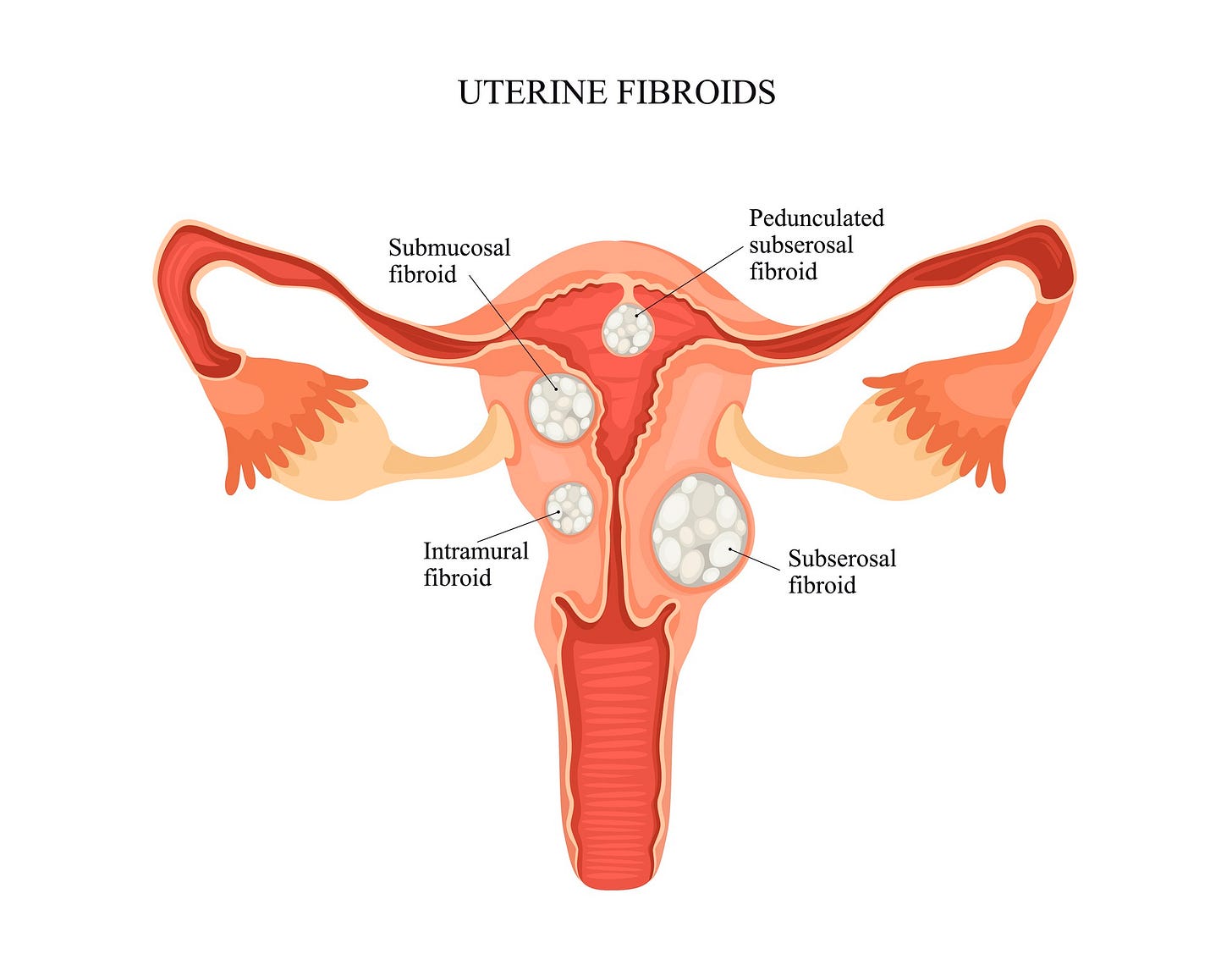

The location of fibroids is broken down into three basic categories, which can help determine if fibroids are involved in symptoms and planning therapy.

Submucosal: these fibroids distort and grow into the endometrium (uterine lining); sometimes, they can hang down by a stalk like a polyp. Rarely, when they are on a stalk, they can even protrude through the cervix. Submucosal fibroids are most likely to contribute to bleeding abnormalities or have an impact on fertility/miscarriage.

Myometrial or intramural: these fibroids are located in the muscle of the uterus.

Subserosal: Here, the fibroids are located close to the exterior surface of the uterus. Sometimes, they are on a stalk and hang off the uterus like a polyp. Fibroids in this location don’t typically cause heavy periods.

The illustration below shows the location of various types of fibroids. There is a more detailed classification system from FIGO (Federation of International Gynecologists and Obstetricians), which categorizes fibroids into eight different classes based on location and how much of the fibroid is protruding into the muscle of the uterus.

How are Fibroids Diagnosed?

If the uterus is enlarged on exam, your provider should be suspicious about fibroids (and, of course other causes as well). Still, sometimes it’s not possible to tell with a pelvic exam, or a pelvic exam may not be feasible or practical for many reasons, so ultrasound is the most common and accurate way to confirm fibroids. Sometimes a saline-infused sonogram (where saline is infused through a catheter from the vagina into the uterus) or an MRI may be needed to get a more precise look at the location and size of fibroids, but these tests are usually only required for planning surgeries and investigating infertility. A CT scan is not helpful as it can’t visualize the uterus in the way that is needed to evaluate fibroids. Sometimes, an MRI can be helpful in the diagnosis of a leiomyosarcoma.

Fibroids and Abnormal Bleeding

How fibroids cause abnormal uterine bleeding is not entirely understood, and there are likely multiple reasons. Fibroids affect the chemical soup in the uterus, for lack of a better term, meaning various growth factors, hormones, and inflammation that are key in triggering menstruation, repairing endometrium, and controlling the behavior of blood vessels. A local chemical trigger helps to explain why some smaller fibroids can cause significant bleeding. Other reasons for heavy bleeding may be how fibroids alter blood flow to the uterus and the physical presence of a fibroid distorts the endometrium, which may affect how the uterus contracts during menstruation.

Treatment Options

The best approach for fibroids depends on the symptoms, their severity, a person’s overall health, whether they are interested in a future pregnancy, and, of course, which therapy they feel is the best for them. Where someone lives may also factor in, as not all medical treatments are available in every country. Age can also factor in as symptoms typically improve in menopause, so a 52-year-old with irregular periods may choose a different therapy than a 45-year-old with regular periods as the 52-year-old has a good chance of her last period happening within the next year, and the 45-year-old does not.

Treatment options can be broadly divided into three groups: medication, minimally invasive procedures, and surgery.

Let’s first consider the medical options.

Six general types of medications are available. Some have more evidence supporting their use than others, and some only help bleeding. Others can bring the full mean deal and reduce bleeding, the size of the uterus, and pain.

*While NSAIDs and tranexamic acid are used for heavy bleeding due to fibroids, they have not been well-studied for this reason.

** GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) antagonists and GnRH agonists work on the pituitary gland in the brain and stop the release of FSH and LH, which are the hormones that trigger the development of a follicle in the ovary and ovulation. They produce a medically-induced but reversible menopause. They are typically given with small amounts of estrogen and a progestin (in doses we use in menopause hormone therapy) to stop symptoms of menopause. In some countries, a lower dose of one of these medications, linzagolix, is available. As it only partially suppresses the hormones, there are no menopause-like symptoms, so taking estrogen and a progestin is not necessary. GnRH antagonists are preferred over agonists as they are oral, and also the GnRH agonists can sometimes flare symptoms before they start to improve.

*** Yes, ulipristal acetate is the same medication in the emergency contraceptive ella®/EllaOne®, although the dose for fibroids is 5 mg a day vs 30 mg for emergency contraption. An advantage of ulipristal is that estradiol levels stay in the mid-follicular range, so there are no symptoms of menopause. Ulipristal acetate is not approved for treating fibroids in the United States, but it is available in some countries under the name Esmya. There are concerns about liver toxicity, which has resulted in its restriction and even removal in some countries. The risk of severe liver injury is about 1 in 100,000. However, no cases of liver injury were seen in the clinical trials for the medication, and no cases of drug-induced liver injury have been linked with ella®. There is a lot of research looking at progesterone receptor modulators for fibroids. In the United States, the right-wing anti-choice agenda could potentially halt research in this area and prevent ulipristal or other similar medications from being studied and eventually approved for this reason.

Procedures for Fibroids: Minimally Invasive and Surgical

Hysterectomy: removing the uterus removes all the fibroids. While this surgery has traditionally been the gold standard, some of the other therapies can also provide excellent results. The major risk of surgery is complications, and there are still unresolved issues about whether a hysterectomy without removing ovaries may increase the risk of heart disease. The concern about heart disease and hysterectomy is from observational studies, and women who have a hysterectomy may also be more likely to have heart disease or health conditions that increase their risk of heart disease, so whether the link between heart disease and hysterectomy is correlation or causation is not known.

Myomectomy, which is surgically removing individual fibroids. Many fibroids can be removed at once. Myomectomy is typically a better choice when there is one (or more) huge fibroids, and the concern is that it (they) may not shrink enough with other therapies. Myomectomy is preferred over minimally invasive procedures for people planning a pregnancy. Removal of the fibroid, with either a myomectomy or hysterectomy., is also recommended whenever there is a concern about cancer.

Uterine artery embolization: under the guidance of x-rays, special material is inserted into the arteries that supply the uterus, causing the blood supply to the fibroids to drop dramatically and, essentially, they die. This can treat bleeding, shrink the size of the uterus, and also help treat pain or pressure from fibroids. Multiple fibroids can be treated at the same time.

Two other minimally invasive procedures are focused ultrasound ablation and radiofrequency ablation. Both techniques use energy to reduce blood flow and kill the cells of the fibroid. The former uses an MRI or ultrasound to guide the energy that targets the fibroids, and the latter is guided by surgical instruments or ultrasound, depending on the location of the fibroids. Both of these procedures require that each individual fibroid be treated. These two procedures are newer, so we have less data.

One big issue with procedures, except for hysterectomy, is the relatively high fibroid recurrence rate. After a myomectomy, within 5 years, about 50% of people will have a new fibroid. This doesn’t mean they will be as big or as bothersome, but people should know so they are prepared. The risk of needing more therapy is higher for people who were younger than 45 when they had their fibroid procedure, which makes sense, as after age 45, within 5 years, about 50% of people will be in menopause.

Fibroids and Menopause Hormone Therapy

Hormones can cause fibroid growth, so menopause hormone therapy can cause the growth of existing fibroids and even cause new fibroids to appear. This can be seen when estrogen is given with a progestin or progesterone or when a progestin or progesterone is given without estrogen. The higher the dose of hormones, the more likely growth is to occur. This isn’t a reason to necessarily avoid MHT. Still, it is a reason to consider starting with the lowest dose of estrogen (a 0.25 mcg estradiol patch or 0.5 mg orally) and a corresponding progesterone/progestin and then increasing if needed if there has been no impact on the fibroids. This is especially true for someone with a larger fibroid. Tibilone, which is not available in the United States, is not associated with the growth of fibroids.

What about Duavee? Premarin plus bazedoxifene (BZA), which is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). Might it be a consideration for women with fibroids? Bazedoxifene degrades estrogen alpha receptors in the breast and endometrium, and estrogen alpha receptors play an essential role in the growth of fibroids. In addition, progesterone/progestin is no longer needed with bazedoxifene, which could be helpful as progesterone/progestin can also stimulate fibroid growth. Raloxifene, which is also a SERM, has been shown to inhibit fibroid growth in some, but not all, studies, so considering Duavee is a valid hypothesis. Unfortunately, there appear to be no studies looking at the impact of bazedoxifene or Duavee on fibroids, so any potential impact on fibroid tissue in the myometrium is unknown, and use outside of a clinical trial is not recommended.

Summary

There are many nuances with fibroids, and of course, I haven’t covered any fertility-related concerns (the best person to address that is a board-certified reproductive endocrinologist who is an infertility specialist). While also not addressed here, it’s important to remember that any bleeding 6 months after the final period should be investigated to rule out endometrial cancer, even when fibroids exist, and some people with bleeding concerns will need to be evaluated for endometrial cancer before their final period.

Hopefully, this review will help you understand more about fibroids and, if you have them, help you advocate for the best medical care.

References

Stewart EA, Laughlin‑Tommaso SK. Uterine Fibroids. NEJM 2024; 391:1721-1733.

Yang Q, Ciebiera M, Bariani MV, et al. Comprehensive Review of Uterine Fibroids: Developmental Origin, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. Endocrine Rev 2021;43:679-719.

Bulun SE. Uterine Fibroids NEJM 2013;369:1344-55.

Huang D, Magaoay B, Rosen MP, Cedars MI. Presence of fibroids on transvaginal ultrasonography in a community-based, diverse cohort of 996 reproductive-age female participants.JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):

e2312701. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.12701

Segars JH, Parrott EC, Nagel JD, et al. Proceedings from the Third National Institutes of Health International Congress on Advances in Uterine Leiomyoma Research: comprehensive review, conference summary and future recommendations. Human Reproduction Update 2014; 20: 309–333.

Borahay MA, Asoglu MR, Mas A, Adam S, Kilic GS, Al-Hendy A. Estrogen Receptors and Signaling in Fibroids: Role in Pathobiology and Therapeutic Implications. Reprod Sci. 2017 Sep;24(9):1235-1244. doi: 10.1177/1933719116678686. Epub 2016 Nov 20.

Templeman C, Marshall SF, Clarke CA, Henderson KD, Largent J, Neuhausen S, et al. Risk factors for surgically removed fibroids in a large cohort of teachers. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(4):1436–46.

Whitaker LHR et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for heavy menstrual bleeding (UCON): a randomised controlled phase III trial. eClinicalMedicine, Volume 60, 101995

Donnez J, Tomaszewski J, Vázquez F, Bouchard P, Lemieszczuk B, Baró F, Nouri K, Selvaggi L, Sodowski K, Bestel E, Terrill P, Osterloh I, Loumaye E; PEARL II Study Group. Ulipristal acetate versus leuprolide acetate for uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2012 Feb 2;366(5):421-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103180. PMID: 22296076.

Donnez, J. Liver injury and ulipristal acetate: an overstated tragedy? Fertil Steril 2018;110: 593 - 595

Palomba, StefanoOrio, Francesco et al. Does raloxifene inhibit the growth of uterine fibroids? Fertil and Steril 2004; 81:1719 - 1720

Srinivasam V, Martens MG. Hormone therapy in menopausal women with fibroids: is it safe? Menopause 2018;25.

I’m so pleased others have access to this info now! I had a hysterectomy (ovaries not removed) 7 years ago after maybe 5 years of ridiculously heavy bleeding. Dr at the time chalked it up to perimenopause until the bleeding got so obstructive to my life that i got an ultrasound and he found a softball sized fibroid. By the morning of my surgery, my hemoglobin was 6, which explained my obsessive (and shameful to me) ice chewing. I wish I’d advocated for myself better all those years by presenting more clear and accurate descriptions of my issue, because just saying “heavy bleeding” to my Dr likely trivialized the epic bleeding I was enduring. Anyway, glad you’re on this earth!

Thank you for this thorough and informative article!