Hormone Testing and Menopause

The Basics and Beyond

Hormone testing is probably one of the top five topics I am asked to discuss in interviews. I’ve addressed it in The Vajenda in the context of tests not recommended by experts (meaning the DUTCH and Clearblue tests), but I thought it might be good to get back to basics.

Why Do We Test for Anything in Medicine?

Broadly speaking, there are two types of tests: screening and diagnostic. A screening test looks at people with no symptoms to identify medical conditions so that early intervention can reduce adverse outcomes. Common tests that you are likely familiar with are cervical cancer screening (HPV testing and Pap smears), mammograms for breast cancer, and blood tests for diabetes. Screening tests are typically done for people at higher risk, with risk determined by age and/or other factors. For example, someone with no risk factors for diabetes should start screening at age 35, but someone with risk factors should be screened earlier. For example, everyone with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) should be screened for diabetes when they are diagnosed with PCOS.

On the other hand, a diagnostic test seeks to understand the cause of symptoms, investigate abnormal results of screening tests, and/or help determine therapy (among many other things). Basically, a diagnostic test helps answer a question, such as why someone has fatigue, the cause of heavy periods, or determining the reason for an abnormality on a mammogram. For example, if someone has fatigue, blood tests to identify potential causes might include a complete blood count (to look for anemia), a ferritin test (to look for iron deficiency), and a thyroid test (TSH or thyroid stimulating hormone). If someone has heavy menstrual bleeding, a diagnostic ultrasound might be ordered to look for a cause.

Menopause: The Terminology

Before we can discuss testing, let’s make sure we are all on the same page language-wise.

Menopause is the planned end of ovarian function and typically occurs between ages 45 and 55. It happens when no more follicles (eggs) in the ovary can ovulate. (The follicles produce high levels of estradiol in the blood). Medically speaking, menopause is just the day of the final period, and everything after is post-menopause. Interestingly, women whose menstrual cycles are longer tend to have a later age of menopause compared with those with shorter cycles.

The time when ovarian function starts to change is known as the menopause transition, which may also be referred to as premenopause. Perimenopause includes the menopause transition and the first year without a period.

This terminology can be a bit kludgy because while in medicine, the date of the last period often matters for research studies, distinguishing between the menopause transition and menopause/postmenopause matters for the individual in determining if someone can still get pregnant and in evaluating bleeding because bleeding after the last period is a potential sign of endometrial cancer. But when it comes to symptoms, such as hot flashes or night sweats, if your final period was 46 or 52 or if you are still having periods, it’s all the same.

While the above language works for studies, it can be messy when talking with patients, so I refer to the last period onwards as menopause and the time before the last period as the menopause transition or perimenopause. And sometimes, when talking with patients in the office, I refer to everything from the menopause transition onwards as the menopause continuum or the menopause experience.

When the final period occurs between ages 40 and 44, the diagnosis is premature menopause. When the final period happens before age 40, the diagnosis is primary ovarian insufficiency or POI. We don’t use the one-year-without-a-period rule here (more on that very shortly).

When menopause occurs because the ovaries were removed, we call it surgical menopause. If this happens, or if the ovaries stop functioning due to chemotherapy before age 45, then this is treated medically as premature menopause.

Menopause is a Normal Physiologic Process

The typical final menstrual period is between ages 45 and 55, so if menstruation stops at age 45 onwards, it is not a sign of anything abnormal; it is how the body is expected to work. Let’s draw an analogy with puberty; if you are 12 and your period starts, it isn’t a surprise because we expect the first period to happen at that age.

A screening test can’t apply to menopause because menopause is a normal biological process. A diagnostic test isn’t needed because, medically, we determine menopause has occurred based on one year of no menstruation for someone age 45 or older. Just as we don’t need a blood test to tell us that a 12-year-old who started menstruating is in puberty, we don’t need a blood test to tell us that a 48-year-old who hasn’t had a period for the past year has experienced menopause. (It is always important to remember that testing for other causes of symptoms, for example, thyroid abnormalities, may be indicated when periods stop at age 45 or older)

What about a 48-year-old whose last period was six months ago? Can a blood test indicate if this is the menopause transition or menopause? First, you don’t need a blood test to start therapy if you have symptoms, so a test isn't of help there. A blood test also can’t reliably tell you if it is safe to stop contraception if that is a concern for you. And a blood test can’t reliably predict when your last period will occur, meaning it can’t tell you with certainty where you are on the menopause continuum. In addition, people can ovulate when they are deep into the menopause transition, and if the blood work happens to catch that, it could look perfectly normal, then you may falsely think you are years from your final period.

What if You Don’t Have Periods?

If you are 45 years or older and have had a hysterectomy, an endometrial ablation, or have a hormone IUD and don’t have periods, if you get symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes or joint pain or brain fog, we’d assume it was the menopause transition/menopause and treat accordingly. If you are considering menopause hormone therapy (MHT) for osteoporosis, neither the FRAX nor the OST (screening questionnaires that help determine the risk of osteoporosis) need your last period. You can find more about MHT and osteoporosis here.

Early Menopause is NOT a Normal Physiologic Process

Going back to our comparison of puberty, if the first period starts at age 12, that isn’t surprising. However, if the first period happened at age four, that is an entirely different story because menstruation is only part of a normal process when it happens at the expected time. This is similarly true for menopause. When someone is younger than 45 and has not had a period in three months, they should have an investigation. The question for our diagnostic test in this situation is, “Why hasn't there been a menstrual period for three months?” There are always exceptions; for example, if someone has polycystic ovarian syndrome and typically only has three periods a year, then evaluating three months of no bleeding in the context of menopause may or may not be needed.

The blood tests that are typically indicated in this situation can identify premature menopause/POI and other causes of skipped periods:

FSH, or follicle-stimulating hormone: Produced by the pituitary gland (in the brain), FSH recruits follicles in the ovaries to grow each cycle and selects the dominant follicle. An FSH level > 25 IU/ml (which is high) is concerning for premature menopause/POI.

Estradiol: The primary estrogen made by the ovary. With premature menopause/POI, the estradiol level is typically < 25 mg/ml, but it can be low for other reasons.

Prolactin: This hormone is also produced by the pituitary glands. When elevated, it can cause irregular cycles or even stop menstruation. Once treated, menstruation will return.

TSH or thyroid-stimulating hormone: Thyroid abnormalities can affect menstruation, and once corrected, menstruation should return to normal.

If the FSH level is high and the estradiol level is low, the results are concerning for premature menopause/POI and should be repeated about a month later. If the FSH is again high and the estradiol is again low, then the diagnosis of premature menopause/POI (depending on age) is typically made. About 5-10% of people with POI can get pregnant, so it’s physiologically different from menopause.

It’s possible to have blood work that looks like premature menopause and then to ovulate several months later and have another period, meaning the blood work may have caught you very close to the end of the menopause transition.

It’s important to diagnose premature menopause and POI because we recommend hormone therapy until the age of 51, the average age of menopause, to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, dementia, and heart disease. At 51, continuing hormone therapy is an individual decision and is thought of as the same as deciding to start MHT for someone who didn’t have premature menopause/POI.

It’s especially important to identify POI as testing as there are health implications, and other testing is indicated. If periods stop before 40 because of surgical menopause or chemotherapy, the workup for POI isn’t needed because the cause of the stopped periods is known.

What if you are younger than 45 years old and have no periods because of a hysterectomy/hormone IUD/endometrial Ablation?

If you have hot flashes or night sweats, you should be tested with the same blood work to rule out premature menopause/POI, but no testing is recommended without symptoms.

What if you are younger than 45 years and are having symptoms that seem like menopause, but menstruation is regular?

I can only write generalizations here because more information is needed.

If your cycles have lengthened by seven or more days and you are over 40 years old, then you are likely in the menopause transition, and symptoms are more likely to be menopause-related. This is even more likely to be the case if you have shorter menstrual cycles. Other causes for the symptoms should still be evaluated, but if none are found, the menopause transition is the likely cause. Hormone levels (FSH/LH) don’t help because if they are normal, you may have just had a normal ovulatory cycle, but you can have those in the menopause transition. If FSH is elevated and estradiol is low, that definitely supports the menopause transition, but it tells you nothing about the timeline.

If you are younger than 45 years, especially if you are younger than 40, and your periods are very regular, yet you are having significant symptoms that seem like menopause, it is wise to have a thorough evaluation for other causes before attributing them to the menopause transition. For example, medications can cause hot flashes and night sweats, and depression can cause brain fog. Testing for FSH and estradiol is generally not helpful when periods are regular because they vary depending on the day of the cycle, and levels are not good predictive tools for whether you are in the menopause transition or how close you might be to menopause. This means they don’t reliably check where you are in the menopause journey (i.e., predict your last period).

Researchers have looked at another test called AMH (Antimullerian Hormone), which tells us about follicle activity (it’s often thought of as a marker for ovarian aging) and, unlike other hormones, doesn’t go up and down during the menstrual cycle. When researchers looked at an ultrasensitive AMH to predict the final period, they found that when levels were < 10 pg/ml (very low), 51% of women ages 42-47 years had their final period within one year, so it was basically a flip of the coin. However, if the AMH level was >100 pg/mL, 97% of women ages 42-47 would NOT have their final period within a year, so a higher level was fairly reassuring for someone not being close to their final period. This means that an AMH level might possibly (with a heavy emphasis on possibly) have some value in evaluating someone who is younger than 45 years with very regular periods yet has symptoms that seem like menopause. If the AMH is high, then premature menopause/menopause transition is less likely, although, again, this is not definitive. Another approach is, after an appropriate work-up for other causes, a three-month trial of MHT or estrogen-containing oral contraceptives could also be undertaken to see if symptoms resolve. Obviously, these cases require a lot of individualization, and hormone tests might rarely be a small piece of the puzzle, but only if the significant limitations of the tests are understood.

Summary

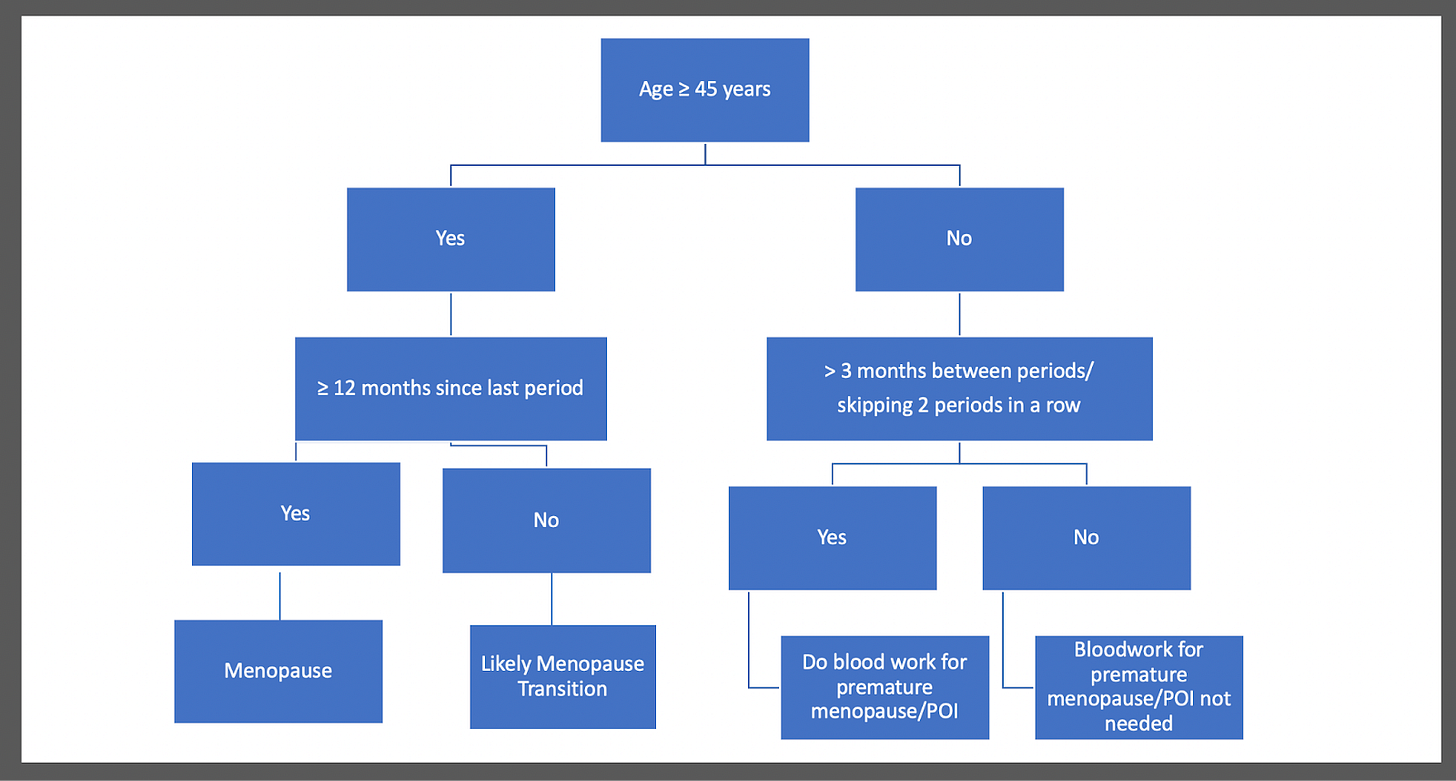

And that’s a deep dive into the when and why of hormone testing in menopause. I’ve tried to sum it all up in a graphic (don’t worry, I’m not going to quit my day job for graphic design).

References

Finkelstein JS, Lee, H, Karlamangla A, et al. Antimullerian Hormone and Impending Menopause in Late Reproductive Age: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 105, Issue 4, April 2020, Pages e1862–e1871.

Primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents and young women. Committee Opinion No. 605. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:193–7.

Ecochard R, Guillerm A, Leiva R, et al. Characterization of follicle stimulating hormone profiles in normal ovulating women Fertility and Sterility 2014;102:237-243.e5.

Paramsothy P, Harlow SD, Nan B, eet al. Duration of the menopausal transition is longer in women with young age at onset: the multiethnic Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2017 Feb;24(2):142-149.

El Khoudary SR, Greendale G, Crawford SL, et al. The menopause transition and women's health at midlife: a progress report from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause. 2019 Oct;26(10):1213-1227.

In a world where it’s hard to know whether going on HRT is the right thing to do to help with moderate perimenopausal symptoms and the long term brain benefits, not to mention to help stem some muscle and bone less, and GPs are poorly informed, I’m struggling to understand what to do as a result of this article. Thank you for addressing early menopause but I guess my question is, what diagnostics can I use to actually get someone in the medical field to help me decide what the right thing to do for my long term health is as I transition, knowing there are real long term implications to loss of estrogen? The world seems primed to let us all just shrivel up after 50 and it’s so frustrating how hard it is to find a healthcare provider who will go down the rabbit hole. You’ve always been the light at the end of the dark tunnel but I’m struggling with what to do…

Thank you so so much for doing a section on women under 40 with periods and symptoms, Jen. I can’t tell you how much it helps to have this information and just to be seen. I’ve a question I’m hoping you might be able to help with on this. How can you know if menopause occurs before 45 if you are on HRT from 39

using merina coil and oestrogen? Is FSH or another test reliable with HRT to diagnose early menopause?

I had regular periods (always short cycle went from regularly 23 to 21 days but had occasional range of 20-27 days) and completely debilitating and worsening symptoms for 5 years after having a baby. Had tests for everything, all normal. Long story short finally got HRT and effect has been incredible. It literally saved my life and gave me back my quality of life. However, as I understand it I’m not in the “early menopause” or POI categories because I had normal tests and still had periods when starting HRT. But I’m 40 now and if I hit menopause before 45 that’s early that makes a difference : it means I’m increased risk for osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease etc. and should continue HRT until at least 51 (and get a DEXA?)? But how would I know if I reach menopause before 45 since Merina stopped my periods? Are tests reliable with HRT? Thanks so much