Many years ago, one of my patients said my superpower was analogies, and this made me very happy because I love analogies and use them often in the office. They are a good way to distill the essence of a complicated physiologic process. During my recent appearance on the Mel Robbins podcast (you can find it here), we delved into menopause. I introduced the analogy of puberty in reverse to help explain this complex phase of life we know as menopause.

Interestingly, this upset some people. Apparently, explaining that menopause was like puberty in reverse in a 45-second clip of a much longer conversation was somehow…a false equivalency, hurtful, promoting a “horrible narrative,” and setting back women’s care as well as denying women hormone therapy. Sigh. An analogy is an analogy; it’s not meant to encompass the totality of every woman’s experiences or be an actual medical definition. Of course, there are clear biological differences between puberty and the onset of menstruation and the menopause transition and menopause, but these two physiologic processes also have some mirror-image resemblances. As everyone has gone through (or will go through) puberty, but only half the population will have menopause, finding a common experience can be a valuable way to introduce a complex physiologic process. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, an analogy has a “resemblance in some particulars between things otherwise unlike.”

While I’m sure I am not the first person to use this analogy, I’d like to take this opportunity to elaborate further. You might learn more about puberty, menopause, and even hormone testing!

Puberty and Menopause are Both Normal Physiologic Events Involving Reproductive Hormones

It is really important to stress that menopause is physiologically normal as there are some people, even some doctors, still clinging to the outdated idea that women were never “meant” to have menopause. Apparently, we women all used to drop dead before the age of 50. As no one in the history of the world has ever said this about men, that belief implies that women are livestock whose useful life ends when they can no longer be bred, which couldn’t be more patriarchal if you tried. Women were too weak to live beyond age 50, but men were not. It truly boggles the mind.

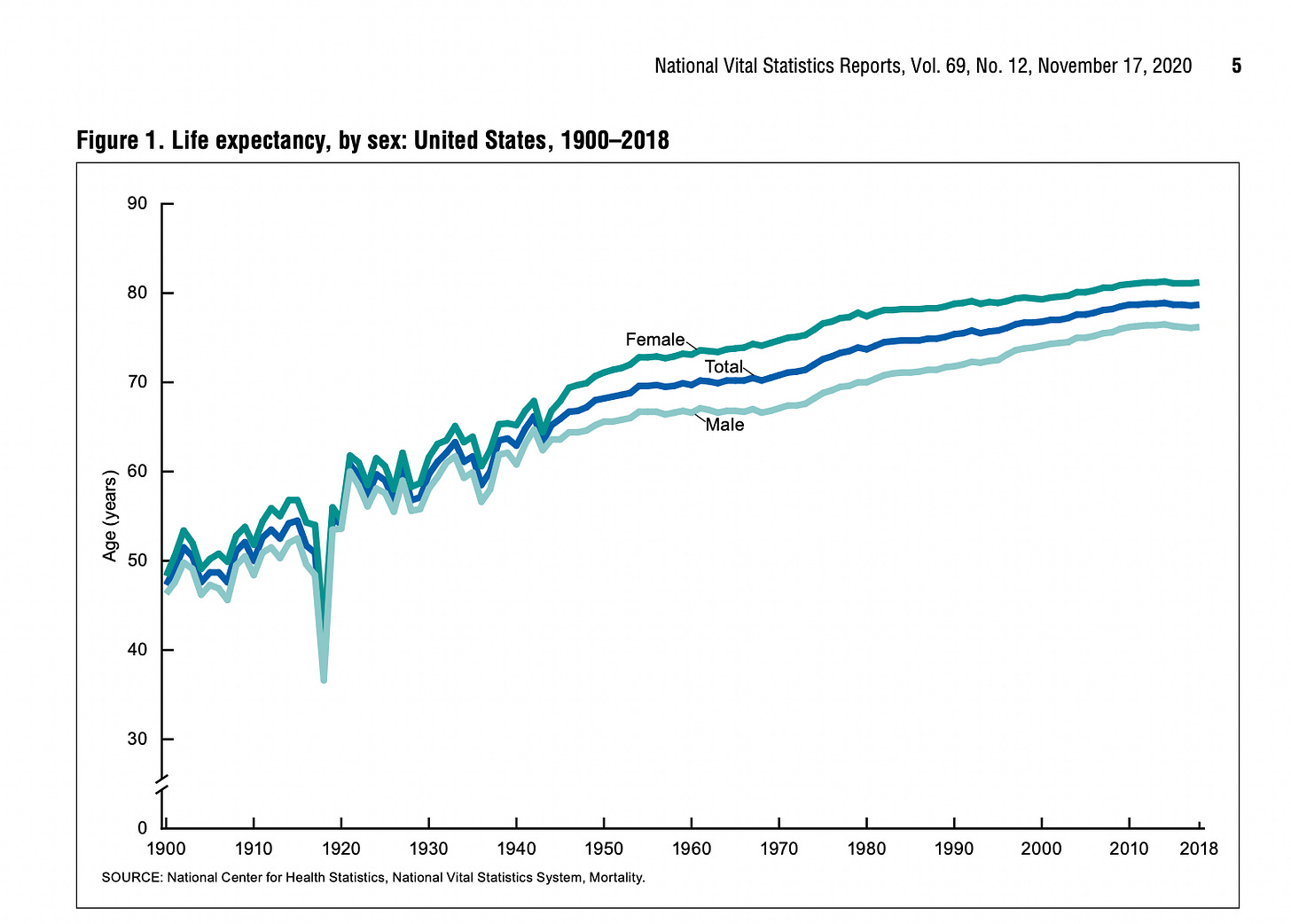

This false idea about the mass culling of women before menopause is also easily disproved. Exhibit A is the historical existence of grandmothers not only in your family tree but also in all kinds of texts from preindustrial society. Exhibit B is that the Ancient Greeks were accurate about the age of menopause, having pegged it at around 50, even way back then. Exhibit C is the average life expectancy in 1900 (before the availability of menopause hormone therapy, antibiotics, and vaccines) was about 48 years for women versus 46 years for men (not that average life expectancy is always the best metric, but it serves a point here). If, before antibiotics, vaccines, hormones, etc., all women were dying before menopause, the average life expectancy for women in 1900 simply could not have been 48 years.

In fact, in 1900, 30% of all deaths were children aged 5 years or younger, so that skews the average downwards for both groups.

This idea that only through the benevolence of modern sanitation and modern medicine can women now outlive their ovaries is a Pharma talking point from the 1960s introduced in the book Feminine Forever, a book that painted menopause as the worst disease imaginable, one that made women unattractive to men.

This is why it is important to establish menopause as a physiologic event, just as we view puberty. Otherwise, the position is that being a menopausal woman is to be in a state of disease, and that is just fucking bullshit. As women have a longer average life expectancy than men, if I wanted to be disingenuous, I could twist the data and say that being a man is a medical condition and the absence of menopause is hurting men.

A Normal Physiologic Process Does Not Have to Mean “A Walk in the Park.”

Let’s take a page from pregnancy. Some people have incredibly easy pregnancies, some people have catastrophic outcomes, and some are in between. I am, sadly, on the catastrophic end. I had triplets, ruptured my membranes at 22 1/2 weeks, delivered my first son, Aidan, who died, and then managed to stay pregnant until 26 weeks when I developed an infection; my two surviving boys were born at 26 weeks, and I developed sepsis. None of that shit show, which we are all still paying the price for 20 years later, means that pregnancy, even a triplet one, is a disease.

When I hear someone discussing pregnancy as a normal physiologic experience, that does not detract from my disastrous experience or anyone else’s disastrous experience. What would be gaslighting would be someone saying pregnancy can never go wrong or have complications or that morning sickness is a fabrication. It would also be wrong to say that pregnancy is a universally terrible experience just because mine was.

It’s important to remember that evolution isn’t affected by individual experiences; it’s about the collective reproducing in enough numbers. In fact, “Barely good enough” could be evolution’s motto. So yes, a normal physiologic process can be plenty fucked up for some. Personally, I think human menstruation is a perfect example of this fuckitude.

The Experiences of Puberty and Menopause Can Both Be on a Spectrum of Not Bad to Awful

I don’t remember much about my puberty; I mean, it was decades ago. But I do remember crying spells, acne, and catastrophically heavy periods with awful cramps and menstrual diarrhea. The acne, heavy flow, cramps, and diarrhea were not just temporary puberty gifts; these were awful things I had to manage for 35 or so years. When we talk about the carnage of puberty, it’s not just about the first period; it is everything that comes along with that package. Just as with menopause, we don’t limit ourselves to what happens during the menopause transition (perimenopause); we also talk about what comes after the final period.

The idea that puberty is a walk in the park and that the comparison somehow belittles the experiences of women in menopause is simply not true. Because in addition to heavy periods, acne, menstrual cramps, and menstrual diarrhea (I mean, that should be enough, right?), puberty can bring the following:

PMS and premenstrual mood dysphoric disorder

Iron deficiency or anemia from heavy periods (iron deficiency affects 40% of women aged 24 and younger)

Endometriosis, which affects 10% of women (often with endometriosis, the very first periods are incredibly painful, whereas with “regular” painful periods, they often aren’t painful for the first year or so)

Menstrual migraines

Polycystic ovarian syndrome and all that accompanies it (affects about 10% of women).

Someone on social media dismissed acne as if it’s not a genuine concern. First of all, as someone who had acne for years, this affected me greatly. Acne can also lead to depression and anxiety. And acne can also affect women in the menopause transition. But seriously, we don’t have to play disease favorites.

Like puberty and the menstrual years, the menopause transition (perimenopause) and menopause can be associated with a range of unpleasant and even awful symptoms and health conditions. The menopause transition and menopause are associated with heavy periods, joint pain, depression, brain fog, and vaginal dryness, to name but a few. Like puberty, some symptoms or conditions will be temporary (brain fog and irregular/heavy bleeding). And just like puberty, some symptoms will last a long time (hot flashes and vaginal dryness).

Some women will find that menopause is so much worse than puberty and their menstrual years, but some women will find menopause a relief as they no longer suffer from PMDD, menstrual migraines, or severe menstrual cramps. There are an infinite number of permutations and combinations of experiences. This isn’t about medical condition oneupwomanship, we can hold space for many things and offer therapy when needed, regardless of where someone is on their menstrual spectrum.

The Hormone Fluctuations in Puberty and Menopause are Like Mirror Images

Puberty marks the start of menstruation, and menopause marks the end, but let’s look a little closer at the “reverse” aspect of the analogy.

Many years before the first period, reproductive hormone levels are low and steady, just as they are years after the final period, but puberty is associated with hormonal chaos (for lack of a better word), and so is the menopause transition. In puberty and the few years after, menstruation goes from irregular to regular, and during the menopause transition, menstruation goes from regular to irregular.

Everyone with ovaries is born with all the follicles (immature eggs) they will have. From birth onwards, multiple follicles develop each cycle and then disappear. With puberty, pulses of hormones from the brain eventually get to the point where they can trigger or catch those follicles before they disappear. If caught, these follicles develop further and start producing estrogen. A dominant follicle emerges, and the first ovulation can theoretically happen. However, this system takes a while to develop fully, so often, the follicles grow and produce estrogen and then disappear, and no ovulation or progesterone appears. Going 60-90 days between periods is quite normal in the first year, and some of the bleeding may result from ovulation, but some periods may occur without ovulation. During years two and three after the first period, ovulation becomes more frequent, and cycles of twenty-one to forty-five days are typical. By age eighteen, most people should have established a menstrual cycle length of twenty-four to thirty-eight days.

Now, let’s skip forward to the mid-thirties, and the average menstrual cycle length (day one of bleeding to day one of bleeding) is still twenty-four to thirty-eight days. While the physiological reasons or triggers for the hormonal changes in the menopause transition are different from those in puberty, one “reverse” similarity is the menstrual cycle length can start to space out by eight days or more. (Normally, a swing of seven days cycle to cycle is normal, so a twenty-five-day cycle, then a thirty-day cycle, then a twenty-six-day cycle, etc., are not medically concerning). Initially, most of these cycles are ovulatory, but over time, more and more anovulatory cycles appear. Menstrual cycles space out even more in the one to three years before the final period, and skipped cycles (going sixty days or more between periods) become common. This means some periods in the menopause transition are associated with ovulation and the withdrawal of progesterone, while others are due to estrogen building up and then the withdrawal of estrogen as the follicle disintegrates without ovulation. And then, finally, the last period occurs.

The first period, puberty, the menopause transition, and the final period are not physiologically the same at all, but they share similarities in that they are times of hormonal transition, one a winding up, if you will, and the other a winding down. They both have anovulatory cycles and cycle irregularly, which occur in almost a mirror image pattern.

Think of Puberty When You Wonder if You Need a Blood Test for Menopause.

If a child had a growth spurt and then started bleeding from her vagina at age eleven, it’s no surprise. It’s puberty and the first period. Before that time, when the child was eight or nine, no one needed to do blood work to see if they were on track for puberty or when their first period might occur. If someone is age thirteen and they are getting their period every 60-90 days, no blood work is needed as irregular periods at this time are expected.

However, if that first period started at age five when puberty is not expected to happen or hasn’t happened by age sixteen, then investigations would be in order. Or if someone is 18 years old and still has periods only every 90 days, then an investigation would be in order.

If someone is 45 or older and their periods become irregular or stop, it is no surprise, as the average age at which the menopause transition starts is 45, and the normal range for menopause is age 45 to 55. Just like in puberty, no blood work is needed (although it may be fair to check for a thyroid condition and, of course, take a full history to ensure these symptoms aren’t due to something else).

If someone is younger than 45 and has skipped two periods, then if this were menopause, it would be early. It is also possible that there could be another cause of irregular periods. In this situation, blood work is indicated to understand the cause of the irregular period/missed periods.

What if the symptoms are hot flashes or brain fog before age 45? Would blood work help here? If the menstrual cycle is regular, it would be important to rule out other causes, for example, iron deficiency or medications as the cause of hot flashes. If there is no other cause, then the early menopause transition may well be the cause. Hormone tests cannot help as they do not predict symptoms or guide therapy. Hormone tests can even be harmful because I hear from many women in their early forties who have symptoms that could be early menopause transition who had blood work to “check,” and it was normal, and they are told they don’t need any therapy because it “can’t” be menopause. Getting a blood test that can’t answer the question is often worse than useless, never mind being a waste of money.

Analogy Explained!

If you have to explain an analogy, does it lose its value, like explaining a joke?

No, I don’t think so. In fact, I think it was a fun exercise, and I hope it helps people see that puberty and menopause are the two menstrual bookends and why I believe this analogy is not dismissive but instead helps us understand the continuum of experiences and offer therapies whenever needed.

References

Arias E, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 69, No. 12, November 17, 2020

Jain V, Munro MG, Critchley HOD. Contemporary evaluation of women and girls with abnormal uterine bleeding: FIGO Systems 1 and 2. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2023;162(Suppl. 2):29–42.

When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Chapter 2, Patterns of Childhood Death in America. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families; Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003.

I appreciate the multitude of ways you explain things--including facts, stories, analogies and utilizing words like fuckitude and fuckery.

I always told my kids that we were a perfect storm of hormones. They were having puberty and I was having puberty backwards. They understood. 🤗