Short Take

There is mounting evidence that vaccination against shingles is associated with a reduced risk of dementia, and several studies suggest this effect may be more robust for women than men.

The data is all observational and is not solid enough to say the vaccine definitely reduces the risk of dementia; all we can say is there is an association between shingles vaccination and a lowered risk of dementia.

The reason to get vaccinated against shingles is to prevent shingles. For an update on the new vaccine, read this post, but consider a potentially reduced risk of dementia as the cherry on top of an already great vaccine.

That’s the TL;DR (too long, didn’t read). If you want the full Happy Meal, read on!

How Could the Shingles Vaccine Reduce the Risk of Dementia?

Well, this is the million-dollar question.

There is quite a lot of research that links shingles with cognitive decline and dementia, although it’s important to point out that not all of the studies are clear there is a link between the two.

If we accept the data to be accurate, there are several hypothesized mechanisms by which shingles could increase the risk of dementia, such as a direct effect of the virus on the nervous system, neuroinflammation, or a harmful impact on blood vessels in the brain. It’s also possible that social isolation from the pain of shingles could play a role. We must also entertain the fact that there is no cause-and-effect link; instead, risk factors for dementia may be the same factors that increase the risk for shingles, although researchers do try to control for this as best they can.

Data with Zostavax

A causative connection between shingles and dementia is a valid hypothesis, so logically, researchers have wondered if the shingles vaccine might reduce the risk of dementia. This would support the hypothesis of a connection and potentially offer a prevention strategy for dementia.

Almost all papers looking at a connection between the shingles vaccine and dementia have looked at the older vaccine, Zostavax, which makes sense because it’s been around since 2006. Several used people vaccinated against influenza, tetanus, or any other vaccine as a control group so they could determine if any protection might be related to a general immune response from vaccination.

One major study was from Wales and included over 300,000 people in a database. The researchers found that Zostavax was associated with a 20% lower risk of dementia. Since then, several papers have looked at this vaccine and a subsequent diagnosis of dementia and found a reduced risk, ranging from 9-43% over the following several years post-vaccination. One study only showed benefits for women.

There are two significant issues with this data. The first is that it is observational. In most studies, people who chose to get the vaccine were compared with people who decided not to get the vaccine, and these two groups could be different in ways that might affect their risk of dementia. For example, Zostavax couldn’t be given to people with compromised immune systems, so it’s possible that people who didn’t receive the vaccine had more medical conditions that weren’t captured in the records, some of which may have increased their risk of dementia or finances may have played a role.

Another possibility is people who were vaccinated against shingles may have been more likely to engage in behaviors that lowered their risk of dementia. For example, vaccinated people may have been more active socially, which is protective against dementia.

In one study, which is still in preprint and not peer-reviewed, researchers used a natural experiment in Wales, where people born before September 2, 1933, were never offered the vaccine, so they compared people who were never eligible to those who were newly eligible, surmising that comparing the just before vaccine eligibility group to the just after group would lead to two groups of people who are fairly similar, as many people before the eligibility date would likely have chosen to be vaccinated had they had the opportunity. This study showed that the vaccine resulted in a 20% lower risk of developing dementia for seven years after vaccination, and the protective effect was greater for women than men.

The other major issue with all of these studies is they are evaluating Zostavax, which I don’t think is even being produced anymore. My understanding is Merck dropped it to focus on COVID-19 vaccines. As Shingrix is a very different vaccine, we don’t know if data about a reduced dementia risk from one vaccine can be applied to the other. If it’s all about reducing the risk of shingles, then Shingrix should outperform Zostavax for preventing dementia. If Zostavax reduced the risk of infection based on the immune response to the vaccine or some other unknown mechanism, then maybe not.

Enter a Very cool and, Dare I say It, Crafty study from 2024

At this point, it seems impossible to perform a randomized controlled trial to evaluate Shingrix for dementia because denying someone a vaccine that reduces their risk of shingles is not ethical. This is where it takes ingenuity and a knowledge of the system to find a workaround.

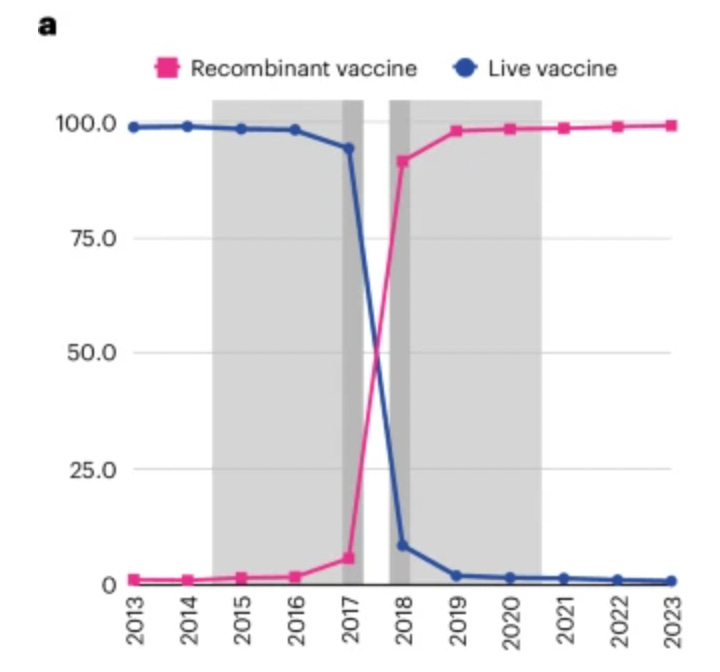

Zostavax was withdrawn from the market in the United States, and Shingrix was introduced surprisingly quickly–over the course of about a year. One vaccine essentially vanished at the end of 2017 and was replaced almost immediately by the other. This provided a natural experiment because, here, everyone chose to be vaccinated against shingles, so they were likely to share more health behaviors and other factors that might not be available in electronic medical records. Here is a cool graph from the study (Taquet et al.) showing how quickly Zostavax (purple) was removed and Shingrix (pink) introduced (the gray blocks show the years studied).

We can never say that two groups in an observational study are equally matched in the way we can with a randomized trial because there are always potentially unknown variables. Is it possible that the Shingrix group, who were early adopters of a new vaccine, are slightly different from those who received a vaccine already on the market for eight years? Sure. However, comparing these two groups, who both chose shingles vaccine, is likely about as good an observational study can get.

This is a large study with data from 62 healthcare organizations, with 103,837 individuals who received Zostavax, matched with 103,837 who received Shingrix. The researchers controlled for multiple variables and compared both vaccines with other vaccines to control for nonspecific effects of vaccination. The result: Shingrix was associated with a reduced risk of dementia over the following six years after vaccination versus the older Zostavax vaccine. The researchers reported this as an increase of 17% in time lived without a dementia diagnosis (or 164 additional days among those later affected) over the six years studied. This effect was more significant for women vs men (women had an increase in time lived without dementia by 22% versus 13% for men). As expected, those who were vaccinated with Shingrix were less likely to develop shingles over the six years of the study than those who received Zostavax, showing the superiority of Shingrix and suggesting, if the results here are genuinely causal, that some of the benefits for dementia may be due at least in part to reducing the risk of shingles.

If we assume that Zostavax already had some beneficial effect against dementia, and if the data from this study is correct, the implication is that Shingrix demonstrated an even greater positive benefit. Let's take a worst-case scenario and assume the benefit of Zostavax on dementia was zero. This newer study is still very suggestive of a benefit. Either way, Shingrix seems to be associated with a reduced risk of dementia over the following six years after vaccination. This study also supports the Zostavax data from the Welsh study, which shows a greater protective benefit for women.

One caveat. If this is an actual vaccine effect, we don’t know if the shingles vaccine is delaying a diagnosis of dementia or lowering the lifetime risk, so longer follow-up is needed.

Where Do We Go From Here?

For an individual making a medical decision, the data about the shingles vaccine relative to dementia is very interesting, and some good observational data suggests a reduced risk, but whether it is an actual cause and effect isn’t known. The data is even more compelling prevention-wise for women, which is interesting considering women have a greater risk of shingles than men, and Alzheimer’s disease is more common among women.

This is definitely a “watch this space” area of medicine, and it’s very exciting. I am interested in seeing how researchers decide to tackle the question of the shingles vaccine and dementia going forward. Until then, get vaccinated against shingles, and know that you may be getting some added protection for your brain that happens to be just coming along for the ride!

References

Gao J, Feng L, Wu B, Xia W, Xie P, Ma S, Liu H, Meng M, Sun Y. The association between varicella zoster virus and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Neurol Sci. 2024 Jan;45(1):27-36. doi: 10.1007/s10072-023-07038-7. Epub 2023 Aug 28. PMID: 37639023.

Shin E, Chi SA, Chung TY, Kim HJ, Kim K, Lim DH. The associations of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus infection with dementia: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024 Mar 12;16(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13195-024-01418-7. PMID: 38475873; PMCID: PMC10935826.

Schmidt SAJ, Veres K, Sørensen HT, Obel N, Henderson VW. Incident Herpes Zoster and Risk of Dementia: A Population-Based Danish Cohort Study. Neurology. 2022 Aug 15;99(7):e660-e668. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200709. PMID: 35676090; PMCID: PMC9484607.

Yeh TS, Curhan GC, Yawn BP, Willett WC, Curhan SG. Herpes zoster and long-term risk of subjective cognitive decline. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024 Aug 14;16(1):180. doi: 10.1186/s13195-024-01511-x. PMID: 39138535; PMCID: PMC11323373.

Schnier C, Janbek J, Lathe R, Haas J. Reduced dementia incidence after varicella zoster vaccination in Wales 2013-2020. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022 Apr 13;8(1):e12293. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12293. PMID: 35434253; PMCID: PMC9006884.

Lophatananon A, Carr M, Mcmillan B, Dobson C, Itzhaki R, Parisi R, Ashcroft DM, Muir KR. The association of herpes zoster and influenza vaccinations with the risk of developing dementia: a population-based cohort study within the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMC Public Health. 2023 Oct 2;23(1):1903. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16768-4. PMID: 37784088; PMCID: PMC10546661.

Shah S, Dahal K, Thapa S, Subedi P, Paudel BS, Chand S, Salem A, Lammle M, Sah R, Krsak M. Herpes zoster vaccination and the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2024 Feb;14(2):e3415. doi: 10.1002/brb3.3415. PMID: 38687552; PMCID: PMC10839537.

Taquet, M., Dercon, Q., Todd, J.A. et al. The recombinant shingles vaccine is associated with lower risk of dementia. Nat Med 30, 2777–2781 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03201-5

Fleming DM, Cross KW, Cobb WA, Chapman RS. Gender difference in the incidence of shingles. Epidemiol Infect. 2004 Jan;132(1):1-5. doi: 10.1017/s0950268803001523. PMID: 14979582; PMCID: PMC2870070.

I've had shingles twice in the last 6-8 years, and after the second go-round I had the Shingrix vaccine as soon as I could. I'm curious how to think about the data you present. That is, does having had shingles increase the likelihood of dementia, up against the (potential) protection of having been (later) vaccinated? I know there are too many unknowns here to say anything with certainty, but it's a scenario I'd be curious to hear your take on.

Great piece; very informative (as always...). And then there's the added question, assuming the protective effect is real -- are people who rec'd Zostavax *and* Shingrix protected even more? It would be nice... (I've had both).