Let's Talk About Genital Herpes

What you need to know to clear up the confusion, erase the stigma, and get the best care

Telling someone that they have genital herpes can be one of the hardest conversations. While some people are not bothered at all, a significant percentage are devastated, and I suspect this is due to an equal mix of the fact the virus is a lifelong infection which understandably bothers a lot of people; lack of factual information about herpes, including the implications and therapies; and stigma, which affects women far more than men (look, misogyny is always going to be an answer). Women are more likely to be judged harshly for having a sexually transmitted infection, and they are more likely to get genital herpes than men and, women are more likely to have recurrences of herpes when compared with men. I remain convinced that if herpes preferentially affected men it would never have been a big deal.

If you know someone who has ever had a cold sore, then you know someone who is almost certainly positive for herpes. It’s highly unlikely that when you see this person with a cold sore that you think of them as diseased or that they should be shamed with a scarlet H. Rather, if you give any thought to it at all, it’s probably some empathy about the sore being painful. If we can be that way about oral herpes, we can adopt that attitude towards genital herpes.

(Note: this post is part of the series on Vulvar and Vaginal Health, for more, check out this post).

Genital Herpes 101

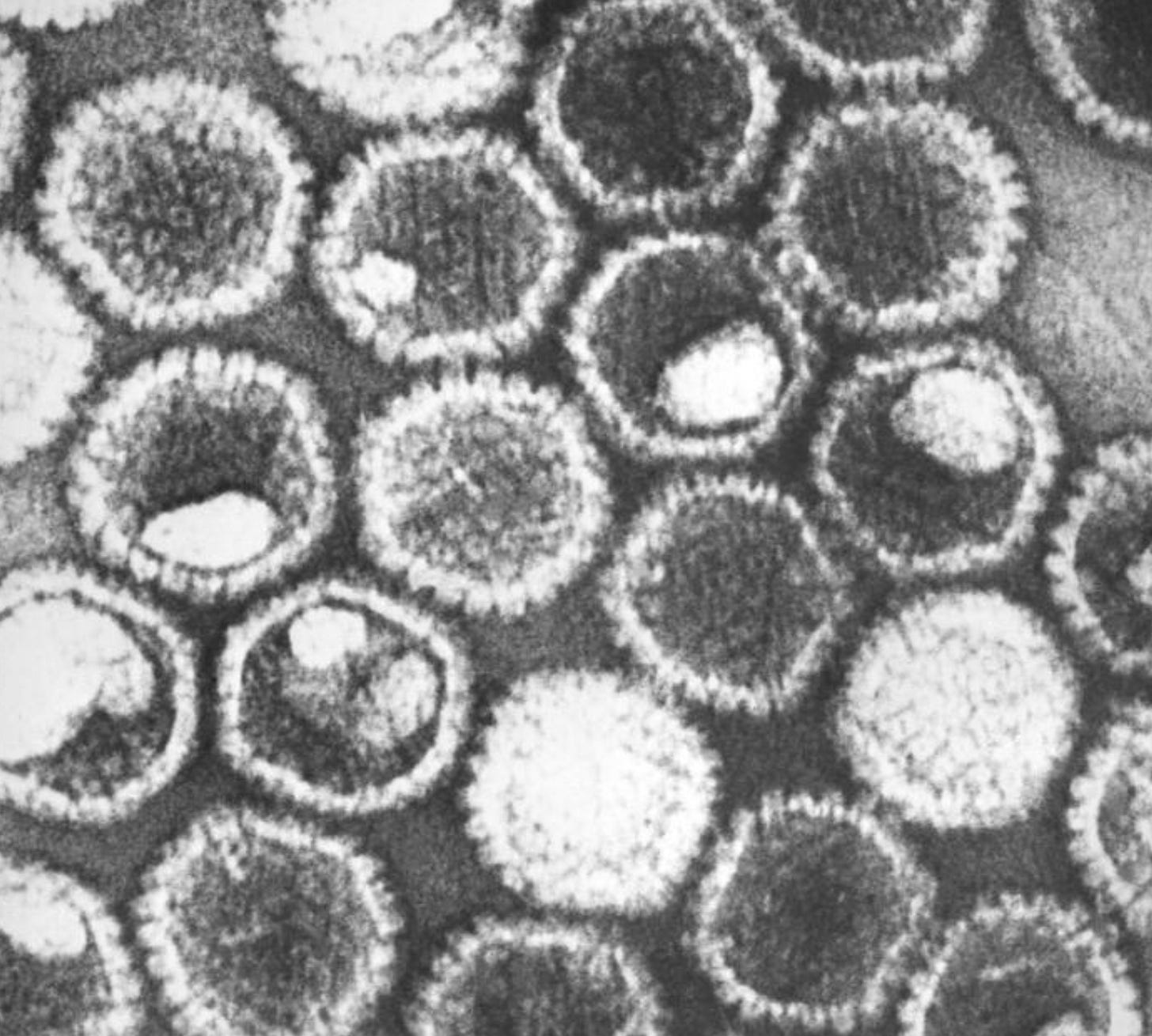

The virus that we commonly refer to as herpes is known as herpes simplex virus or HSV. There are many different types of herpes viruses, and one of the defining characteristics is the phenomenon of latency, which means after the initial infection the virus goes into hiding in cells, like a hibernation, and then can be triggered to reactivate later. Chicken pox (varicella zoster virus) and infectious mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus, or EBV) are also herpes viruses, and these viruses can also reactivate at a later date. Most people know about varicella zoster reactivation, which is known as shingles.

There are two distinct herpes simplex viruses, HSV-1 and HSV-2, and they can both infect the mouth or the genitals. When one of the viruses affects the vulva, vagina, anus, perineum, penis, or scrotum it is considered genital herpes and when herpes affects the mouth or lips, it’s oral herpes (which we won’t be discussing further).

We used to believe HSV-1 only infected the mouth and HSV-2 the genitals, but we’ve known for decades that genital herpes can be caused by either HSV-1 or HSV-2, although the prevalence of genital HSV-1 infections is increasing and currently, about 50 percent of new genital herpes infections are due to HSV-1. The main theory is that fewer people are catching HSV-1 as children, possibly because of less overcrowding or better nutrition and so instead of getting HSV-1 early on, the first exposure is later in life, during oral sex. Infection with herpes produces antibodies, so when people get oral HSV-1 as a child, they have antibodies that usually protects them from infection elsewhere if exposed later. Interestingly, if someone has oral HSV-1 first and is exposed later to genital HSV-2, the HSV-1 antibodies do not reduce their chances of catching HSV-2 on the genitals, but the antibodies do reduce the risk that a new HSV-2 infection will cause symptoms (prior HSV-1 infection modifies the severity of a subsequent HSV-2 infection). When someone has genital HSV-2 first, this reduces their risk of acquiring genital HSV-1 if exposed.

An estimated 846 million people ages 15-49 have either genital HSV-1 or 2, and about 205 million people have had genital ulcers due to herpes (not everyone with the virus gets outbreaks). Worldwide, about 67% of people are positive for HSV-1 and 13% for HSV-2.

The First Infection

A break in the skin, usually microscopic, allows HSV to enter the body. The virus is particularly adept at evading the immune system, so it quickly starts what amounts to a viral pop-up shop in the deeper layers of the skin, where it replicates. The viral particles spread quickly to the ends of sensory nerves (nerves that transmit and receive information about sensation are different from motor nerves that control how our muscles move), traveling up the nerves to a structure called dorsal root ganglion, which is a cluster of the cell bodies of the sensory neurons. Here in the dorsal root ganglion the virus establishes a permanent home.

Sometimes the initial viral replication in the skin leads to an episode or outbreak, which classically starts as redness, then progresses to a painful bump, which then forms a blister that then turns into an ulcer and then eventually scabs over. Not all outbreaks are classic, so people may be mistakenly diagnosed with another condition, such as inflammation of a hair follicles or a yeast infection. There is also another scenario with the first infection–no lesions at all. It’s important to know that many times with a first infection the virus causes no symptoms and goes completely undetected as it travels up the nerves. This is how so many people carry HSV-1 or HSV-2 and have no idea they have the virus because they never had an outbreak with their first infection. In one study, 80% of people with antibodies to HSV-2 had never had a genital outbreak, so did not know they had previously been infected (as HSV-2 is an uncommon cause of oral herpes, most of these infections would likely have been acquired though genital transmission).

From a habitat standpoint, HSV-1 prefers the mouth and HSV-2 prefers the genitals. This means that when HSV-1 occurs on the genitals it is less likely to recur than when the infection is in the mouth. And the reverse is true for HSV-2, which is very unlikely to cause an oral lesion or to recur in the mouth versus the genitals. The risk of shedding, and hence being contagious, for someone without symptoms is much less with HSV-1 on the genitals versus HSV-2.

The First Episode

This is first time someone has lesions, and it may also be called the first outbreak. The lesions can often extend over a large area, typically both sides of the vulva, and there can be redness, swelling, vaginal discharge and a lot of pain. Occasionally, the pain can be so bad that it is hard to urinate. Flu-like symptoms, such as headache, chills, fatigue, and generally feeling awful are quite common. It can take 2-3 weeks for the first outbreak to clear completely when untreated.

People used to think that a typical first outbreak meant the virus has recently been acquired and this was proof of a new or a primary infection. However, a study where herpes researchers evaluated women with their first outbreak and they felt confident that things were bad enough that this represented a primary or first infection, they were only correct once out of 23 times. This means the first episode can be a primary infection, as discussed above, but it is even more likely that it is represents a reactivation of a virus that is already present.

Recurrence Episodes

Periodically, the HSV-1 or 2 virus wakes up and viral particles travel back down the sensory neurons, like electricity down a wire, to the skin, and this is known as a reactivation or a recurrence. One of two things will happen: there is shedding of the virus, meaning viral particles are produced and these are infectious, but there is no pain or sores; or the viral particles produce a sore (there will also be shedding). Often people have what are called prodromal symptoms before a visible recurrence, which is tingling, pain, or burning a day or so before the lesions appear.

Compared with the first episode there tend to be fewer lesions with less severity with recurrences. It typically takes 1-2 weeks for a recurrence to completely clear without medication. This fact that a reactivation can produce shedding and no symptoms, is an important point, because this is how people unwittingly pass the infection along. They may not even know they even have herpes because they may have never had an outbreak that manifested with sores, they have simply been asymptomatically shedding the virus on and off.

Understanding initial infection, first episode, and recurrences is crucial because the first appearance of an ulcer (sore) does not necessarily mean this is a first infection; the first ulcer could be a new infection, but it could also be the first visible reactivation a.k.a first episode of a virus acquired months or even years prior.

What Are the Consequences of a Genital Herpes Infection?

· The cost of medical appointments and medication

· The pain of the sores and other symptoms

· The emotional toll of an infection and fears about disclosing to partners

· With genital HSV-2 there is an increased risk of acquiring HIV if exposed. This is likely from the inflammation due to reactivation of the virus. Some data suggests genital HSV-2 increases the risk of acquiring HIV threefold if exposed.

· Neonatal herpes, which happens during delivery and less commonly during pregnancy. This is a very serious infection for a newborn, and without appropriate therapy mortality is high. Most cases of neonatal herpes occur when genital herpes is acquired during pregnancy closer to delivery, because in this situation there hasn’t been time for protective antibodies to develop and be passed along to the newborn. Neonatal herpes can also develop from a reactivation of a previous infection.

Diagnosing Herpes

Genital herpes can be diagnosed clinically, meaning a health care professional looks at the sore and says, “That looks like herpes.” This is often inaccurate, because, as previously mentioned, an outbreak may not look like classic herpes., so lots of infections could be missed. For this reason, and because knowing if the cause is HSV-1 or HSV-2 can help predict risk of recurrence, the recommendation is to take a swab from the lesion (this will be painful but should only take a few seconds) which detects herpes DNA. Culture is also an option, but it can miss the virus, especially if the sore has started to crust over, so the DNA tests are preferred.

There are also blood tests, but there are some important nuances. Blood tests identify antibodies to herpes, which signifies a previous infection. There are two types of antibodies: IgM, which are produced very quickly after an infection, and IgG which take a while to develop. IgM antibodies for herpes are not reliable and should never be ordered.

The IgG antibody test must be type specific, meaning it is able to distinguish accurately between antibodies for HSV-1 and HSV-2. The test is most commonly an enzyme-linked immunoassay; a Western Blot is the gold standard but is not readily available. IgG antibodies can take up to 12-16 weeks to develop and there can be false positives and false negatives, so these factors must be considered when interpreting the results. Here are 4 common scenarios with blood tests:

1. A first episode: the lesion tests positive for HSV-2 and the antibody test is positive for IgG for HSV-2. This is a reactivation/recurrence.

2. A first episode: the lesion tests positive for HSV-1 and the antibody test is positive for HSV-1. This is almost certainly a recurrence as people generally don’t get both oral and genital herpes.

3. A first episode: the lesion tests positive for HSV-2 and the antibody test is negative for HSV-2. Generally, this is considered a first infection. If the antibody test is repeated in 12-16 weeks it should now be positive.

4. A first episode: the lesion tests positive for HSV-1 and the antibody test is negative for HSV-1. Generally, this is considered a first infection. If the antibody test is repeated in 12-16 weeks it should now be positive.

A positive antibody test provides more clarity than a negative one.

Treatment

There are three drugs to choose from, and they are very similar: acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. These are very safe medications and there is a very low risk of developing resistance. With a first outbreak of genital herpes the medication should be started as soon as possible, and 7-10 days of therapy are recommended:

• Acyclovir 400 mg orally three times a day for 7–10 days

• Valacyclovir 1 g orally twice a day for 7–10 days

• Famciclovir 250 mg orally three times a day for 7–10 days

These medications can also be taken during recurrent outbreaks but should be started within one day of the onset of the lesion or preferentially during tingling or burning before the outbreak. This medication shortens the duration of the lesions by 1-2 days when started during the prodrome. There are multiple different regimens, anywhere from 1–5 days depending on the drug and the dose. Not everyone will decide to take medication for a recurrence. For some people the recurrence isn’t bothersome, and if they elect not to treat, that is fine. For others, recurrences are very painful and/or emotionally traumatic and treatment is preferred.

Suppressive Therapy and Prevention

Instead of waiting for recurrences, there is the option of suppressive therapy. When someone has six or more outbreaks a year, taking anti-viral medication daily, reduces the number of outbreaks of HSV-2 by 70–80%. Suppressive therapy also reduces shedding of the virus by 94%, and can reduce the risk of transmitting the virus to others by 50%. Another consideration for suppressive therapy is for someone w at higher risk of acquiring HIV; given the association between HSV-2 and HIV, antiviral suppression of herpes makes sense. The doses for suppression for people without HIV and who are not pregnant are:

• Acyclovir 400 mg orally twice a day

• Valacyclovir 500 mg orally once a day, increase to 1 g a year for people who continue to get outbreaks on the lower dose or who had 9 or more recurrences a year

• Famciclovir 250 mg twice a day

As the risk of recurrence for genital HSV-1 is less than for genital HSV-2 and most of the data for suppression therapy is for HSV-2, it isn’t known how much of a benefit suppressive therapy provides for HSV-1 infection on the genitals. Considering how safe these medications are, suppressive therapy isn’t wrong, I often recommend it for 6-12 months after a first outbreak as the risk of shedding is likely higher, but admittedly that is anecdotal.

In addition to antiviral therapy, condoms reduce the risk of transmission from cis-men to cis-women by 96%, and they reduce the risk of transmission from cis-women to cis-men by 65%. Dental dams likely reduce the risk of transmission with oral sex, but by how much isn’t known. Pubic hair removal may also be associated with an increased risk of acquiring genital HSV infections. The data isn’t that great, but the hypothesis is that pubic hair removal leads to microtrauma, which increases the risk of acquiring the infection if exposed, and it certainly is biologically plausible

Genital herpes remains one of the most misunderstood and stigmatized health conditions, despite being a widespread and manageable viral infection. As women bear a greater burden with genital herpes, this almost certainly is a contributing factor to the stigma. What people should know is that herpes is common, silent first infections are typical, and the first outbreak can be a new infection or a recurrence. Knowing the type of herpes can help determine the risk of recurrence, which can be helpful. There is effective medication when needed and a couple of good strategies to reduce the risk of transmission.

I’m often asked why herpes blood tests aren’t part of a routine sexually transmitted infection panel, so stay tuned, we’ll tackle that in the next post.

References

American Sexual Health Association https://www.ashasexualhealth.org/new-research-highlights-need-improved-herpes-diagnostics/

Van Wagoner N, Qushair F, Johnston C. Genital Herpes Infection: Progress and Problems. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2023 Jun;37(2):351-367. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2023.02.011. PMID: 37105647.

CDC STI Guidelines (I checked and nothing has changed, so still reliable for now). https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/herpes.htm

Wald A. Genital HSV-1. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:189–190. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019935

Hensleigh PA, Andrews WW, Brown Z, Greenspoon J, Yasukawa L, Prober CG. Genital herpes during pregnancy: Inability to distinguish primary and recurrent infections clinically. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89:891-5

Singh A, Preiksaitis J, Ferenczy A, Romanowski B. The laboratory diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infections. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005 Mar;16(2):92-8. doi: 10.1155/2005/318294. PMID: 18159535; PMCID: PMC2095011.

WHO Factsheet Herpes https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/herpes-simplex-virus

Clarke E, Patel R, Dickins D, et al. Joint British Association for Sexual Health and HIV and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists national UK guideline for the management of herpes simplex virus (HSV) in pregnancy and the neonate (2024 update). International Journal of STD & AIDS 2024, Vol. 0(0) 1–20

Patel R, Green J, Moran B, et al. 2014 UK national guideline for the management of anogenital herpes. Int J STD AIDS. 2015; 26(11): 763–776.

Copas AJ. An evidence based approach to testing for antibody to herpes simplex virus type 2. Sex Transm Infect 2002; 78: 430–434.

I acquired genital herpes sometime in my 20s - did not know at the time what it was and was too embarrassed to ask a doctor. It was finally diagnosed in my late 30s because I used cortisone to treat the itching which caused huge welts, and finally saw a doctor. I took valacyclovir at the time but then stopped after the initial treatment for that one episode, and tried to treat outbreaks with lysine (which didn't work). In 2007, at age 54, I developed Ménière's disease, diagnosed by a very well known ENT. He asked if I had ever been diagnosed with Herpes, because he believed the virus causes or perhaps triggers Ménière's disease. He prescribed 1g/day of valacyclovir basically for the rest of my life. My hearing has been fairly well preserved; I stopped having episodes of vertigo after about 6-12 months of treatment with valacyclovir which could occur anywhere, any time (I still feel woozy at heights but nothing spins); I do have constant tinnitus but I've trained myself to pretty much ignore it. I've never had another herpes outbreak - I'm now 71. I wonder if you've heard of this potential connection between the herpes virus and Ménière's disease?

It was such a relief to find the book "The Good News About the Bad News" by Terri Warren when I contracted HSV-2 many years ago. Grateful for those like you who do their part to shed light on this subject now as well.