Scaring Women About Hormones Makes Copy

Thoughts on how the Press Handles Studies about the Risks of Hormonal Contraception

There is a new study looking at the association between the levonorgestrel IUD and breast cancer, and, as expected, it has spawned many headlines, some that are accurate and some that are absolute click-bait (come on New York Times and MedPage Today, like WTF?).(1)

I’ve been fielding a lot of questions because A) breast cancer headlines are scary, and B) levonorgestrel IUDs are popular. Many women use the levonorgestrel IUD for contraception, but they are also a veritable GYN Jill-of-All-Trades because we also use them to manage heavy bleeding, treat painful periods and/or endometriosis, and prevent endometrial cancer (either for someone who is at a higher baseline risk or as part of menopause hormone therapy), so, understandably, many women have questions.

The Study

The authors used a database in Denmark to look at breast cancer risk associated with the use of the levonorgestrel IUD by comparing women who used that method with those who were not using any form of hormonal contraception. This study also accounts for other hormone exposures to help ensure any effect seen would be related to the IUD. Failure to account for this has been a previous criticism of similar studies.

The finding was a 40% increased risk of breast cancer with the levonorgestrel IUD regardless of the duration of use (reported as a hazard ratio of 1.4; remember that number). This translates into an extra 14 cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women using a levonorgestrel IUD for 5 years. When the researchers looked at the difference in duration of IUD use, for example, 5 yr vs 10 or 15 years, the difference in risk wasn’t statistically significant.

There are a few issues with the study. This doesn’t make it good or bad, it’s just important to understand. This study did not break down risk by type of hormonal IUD, which would have been interesting as the amount of levonorgestrel that initially enters the blood varies. Biologically, it’s hard to reconcile the same risk with the higher dose IUDs. Still, of course, it’s not impossible if, for example, only a minute amount of progestin were needed to trigger risk. So, like many studies, this paper generates more questions. In addition, the study did control for some major known risk factors for breast cancer, such as alcohol use, smoking, or a family history of breast cancer. As the women were not randomized, it’s possible women with a slightly higher risk of breast cancer were more likely to select a hormone IUD than those who chose not to use hormonal methods.

This Isn’t A New Finding, And Studies are Conflicting

This is what is frustrating from a press-attention standpoint. We have known for some time that there is a small increased risk of breast cancer associated with estrogen-containing hormone birth control, and some recent studies (which have been covered by the press) suggest that the same risk may be present with progestin-only methods (one which I previously covered here). Does this study contribute to the body of knowledge? Yes. Does it general important questions? Yes. Is it revelatory to the general population? No. Meaning this study is not news and doesn’t change what we know.

A previous study from Denmark suggested that hormonal IUDs were associated with a 21% increased risk of breast cancer. Another study pegged the increased risk of breast cancer with the IUD to be about 32%. However, it’s equally important to note that several studies show no increased risk of breast cancer with levonorgestrel IUDs. Remember, all of this data is from observational studies and so it’s tricky. Even if we assume the data that shows an increased risk of breast cancer with the levonorgestrel IUD is the correct result and the ones that show no risk to be incorrect (and that’s a leap, but just go with it), it’s still impossible to truly assign cause and effect, so we can only say there is an association.

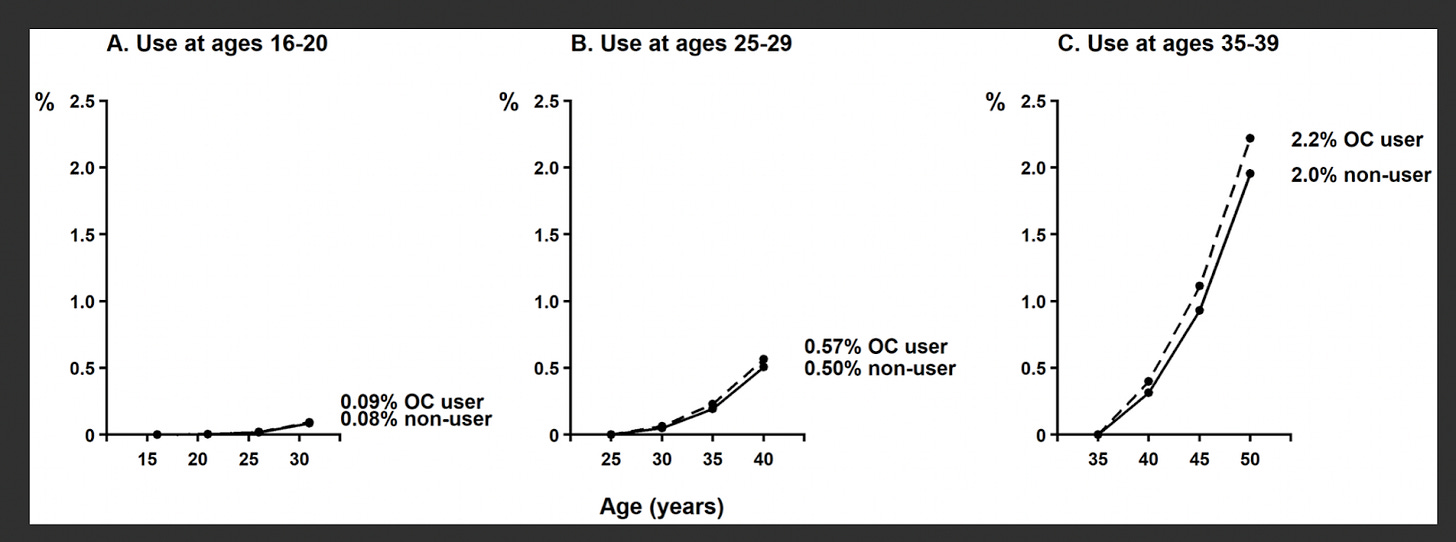

A recent meta-analysis tried to put the risk of breast cancer with hormonal contraception into perspective. While the chart below from that meta-analysis pertains to oral contraceptives, this meta-analysis found the slightly increased risk with oral contraceptives to be similar to the risk with a hormonal IUD, so I think it’s fair to show the visual because it’s so good. The chart shows the absolute risk (%) of breast cancer over a 15-year period associated with 5 years of use of oral contraceptives and then over the next 10 years of non-use. Looking at the highest risk group, women ages 35-39 (because breast cancer risk increases with age), 5 years of oral contraceptive use is associated with a 2.2% risk of breast cancer over the next 15 years vs 2.0% for those who had not used the pill.

The Health Benefits

Contraception obviously protects the user from the risk of pregnancy, which in itself may be important enough to bear the burden of a very small increased risk of breast cancer (assuming the risk is true). But preventing pregnancy also prevents medical complications of pregnancy, such as maternal mortality, blood transfusions, blood clots, preeclampsia, and pelvic floor disorders, to name but a few. I maintain that if pregnancy were a drug it would have one hell of a black box warning. Let’s look at the risk of blood clots during pregnancy, which one paper reports as 12.2 per 10,000 pregnancies vs 2 per 10,000 women who are not pregnant. Blood clots can be serious, and they account for about 9% of maternal deaths in the United States and yet it’s rarely news worthy to the press or relevant to social media, the later likely because no one has figured out how to sell a blood-clot preventing cleanse. Yet.

Besides all of the health benefits of preventing unwanted pregnancies and controlling heavy bleeding and pelvic pain, a hormonal IUD is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of endometrial cancer.

Finally, I am always fascinated by the fact that the press seem to be uninterested in the short-term increased risk of breast cancer associated with pregnancy (it peaks about five years after delivery). Over the years, pregnancy subsequently has a net protective effect, but initially, there is an increased risk. One paper calculated a hazard ratio of 1.8 for pregnancy-related breast cancer (nows the time to recall that 1.4 hazard ratio from the latest hormonal IUD/breast cancer study). If the breast cancer risk associated with an IUD is worth discussing, why isn't the risk associated with pregnancy? And why is it never mentioned in the articles?

I thought it would be interesting to find a recent-paper on the pregnancy-related breast-cancer risk and compare it’s popularity with this latest paper on the breast cancer risk and the levonorgestrel IUD. It’s easy to do this by looking at the Altimetric score, which tracks meaningful online engagement (basically a measure of a paper’s popularity). I found a study published in JAMA Network Open in August that looked at pregnancy-related factors and breast cancer risk. The article has been viewed 1,891 times since August of this year and wasn’t mentioned once in the press.

Now, let’s look at the research letter we are discussing in JAMA on breast cancer risk associated with hormonal IUDs. In the last seven days, it has been viewed 17,364 times, is in the top 5% of research outputs scores by Altimetric, and was mentioned in 76 news stories by 68 news outlets (at my last count on Oct 23 at 10:40 am PST).

If even a very small risk of breast cancer seems to matter to all these news outlets, then it’s curious why, when that risk extends to understanding the risk that may be related to pregnancy, it’s all of a sudden not interesting at all.

Actually, it’s not surprising at all. Risks seem to be ignored by our society when those risks benefit the patriarchy.

The Take Away

There is possibly a small increased risk of breast cancer associated with the levonorgestrel IUD, but this isn’t new information and it’s important to point out that not all studies have found this association. Even if we assume the association is true, based on the available data, we still can’t say with certainty if there is a cause and effect. If there is a cause and effect, the magnitude of the effect is very small.

Several studies have shown the association, so it’s worth discussing. Given the low magnitude of the risk versus the benefits of the IUD, the benefit to risk ratio will almost certainly be favorable for most people.

(By the way, this data can’t tell us how this risk might apply to women using the levonorgestrel IUD as part of their MHT, and we shouldn’t extrapolate to apply to those groups).

References

Mørch LS, Meaidi A, Corn G, Hargreave M, Wessel Skovlund C. Breast Cancer in Users of Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine Systems. JAMA 2024; October 16.

Mørch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, et al. Contemporary Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:2228-2239.

D Fitzpatrick, K Pirie, G Reeves, J Green, V Beral. Combined and progestagen-only hormonal contraceptives and breast cancer risk: A UK nested case–control study and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine 20(3): e1004188. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004188

Jareid M, Thalabard JC, Aarflot M, Bøvelstad HM, Lund E, Braaten T. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system use is associated with a decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer, without increased risk of breast cancer. Results from the NOWAC Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Apr;149(1):127-132. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.02.006. Epub 2018 Mar 2. PMID: 29482839.

Soini T, Hurskainen R, Grénman S, Mäenpää J, Paavonen J, Joensuu H, Pukkala E. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and the risk of breast cancer: A nationwide cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(2):188-92. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1062538. Epub 2015 Aug 4. PMID: 26243443.

Siegelmann-Danieli N, Katzir I, Landes JV, Segal Y, Bachar R, Rabinovich HR, Bialik M, Azuri J, Porath A, Lomnicky Y. Does levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system increase breast cancer risk in peri-menopausal women? An HMO perspective. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018 Jan;167(1):257-262. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4491-2. Epub 2017 Sep 14. PMID: 28913650.

Backman T, Rauramo I, Jaakkola K, Inki P, Vaahtera K, Launonen A, Koskenvuo M. Use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Oct;106(4):813-7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000178754.88912.b9. PMID: 16199640.

Dinger J, Bardenheuer K, Minh TD. Levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices and the risk of breast cancer. Contraception. 2011 Mar;83(3):211-7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.11.009. Epub 2011 Jan 7. PMID: 21310281.

McDonald JA, Liao Y, Knight JA, et al. Pregnancy-Related Factors and Breast Cancer Risk for Women Across a Range of Familial Risk. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(8):e2427441. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.27441

Bukhari S, Fatima S, Barakat AF, Fogerty AE, Weinberg I, Elgendy IY. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and postpartum period. Eur J Int Med 2022;Volume 97, 8 - 17.

Hazel B. Nichols, Minouk J. Schoemaker, Jianwen Cai, et al. Breast Cancer Risk After Recent Childbirth: A Pooled Analysis of 15 Prospective Studies. Ann Intern Med.2019;170:22-30. [Epub 11 December 2018]. doi:10.7326/M18-1323

“I maintain that if pregnancy were a drug it would have one hell of a black box warning.” 💯

Thank you for this. Maybe it’s because it’s October, and because I’m awaiting biopsy for a suspicious finding from high risk screening, but I’m beginning to feel like I’m drowning in breast cancer awareness and all kinds of confusing and conflicting information about what constitutes risk — even from what I would consider respectable sources like the NYT.

I do hope you’re going to get to that post you mentioned a while ago getting into the science of “high risk breast cancer” and how that should influence individual health care decisions.