The Basics of Menstrual Blood

And that viral TikTok claim about stopping periods with ibuprofen and Jello.

Over on Threads, Instagram's answer to Twitter, there has been a lot of conversation about menstruation. Which is great because A) it’s great and B) it means the algorithm is working for me! The conversation that I was part of was about nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to reduce menstrual flow (which they do, and we’ll get to that shortly), but then someone wondered about the volume of blood and someone else wondered if medications to reduce flow might be harmful if it resulted in blood or uterine lining being left behind. When no one really talks about the actual biology of menstruation, and it’s rarely taught in schools, how would you know?

Typically, when one person has a question, many people have the same one, so I thought now would be a great opportunity to talk about menstrual fluid and how NSAIDs work to reduce flow, as well as that bizarre TikTok hack that claims that ibuprofen and gelatin or Jello (and sometimes a lemon, depending on the version) can delay or stop your period. Spoiler alert: it can’t. Yes, I know you are all shocked, simply shocked that a TikTok menstrual hack involving Jello isn’t correct.

The Basics of Menstrual Fluid

What comes out of your body during menstruation is menstrual fluid, but most people call it blood. And it is totally okay to call it blood. But to avoid confusion and hopefully clear up any pre-existing confusion, we will get technical and refer to what comes out of the uterus during menstruation as menstrual fluid. Blood is a significant component, but it’s not just blood.

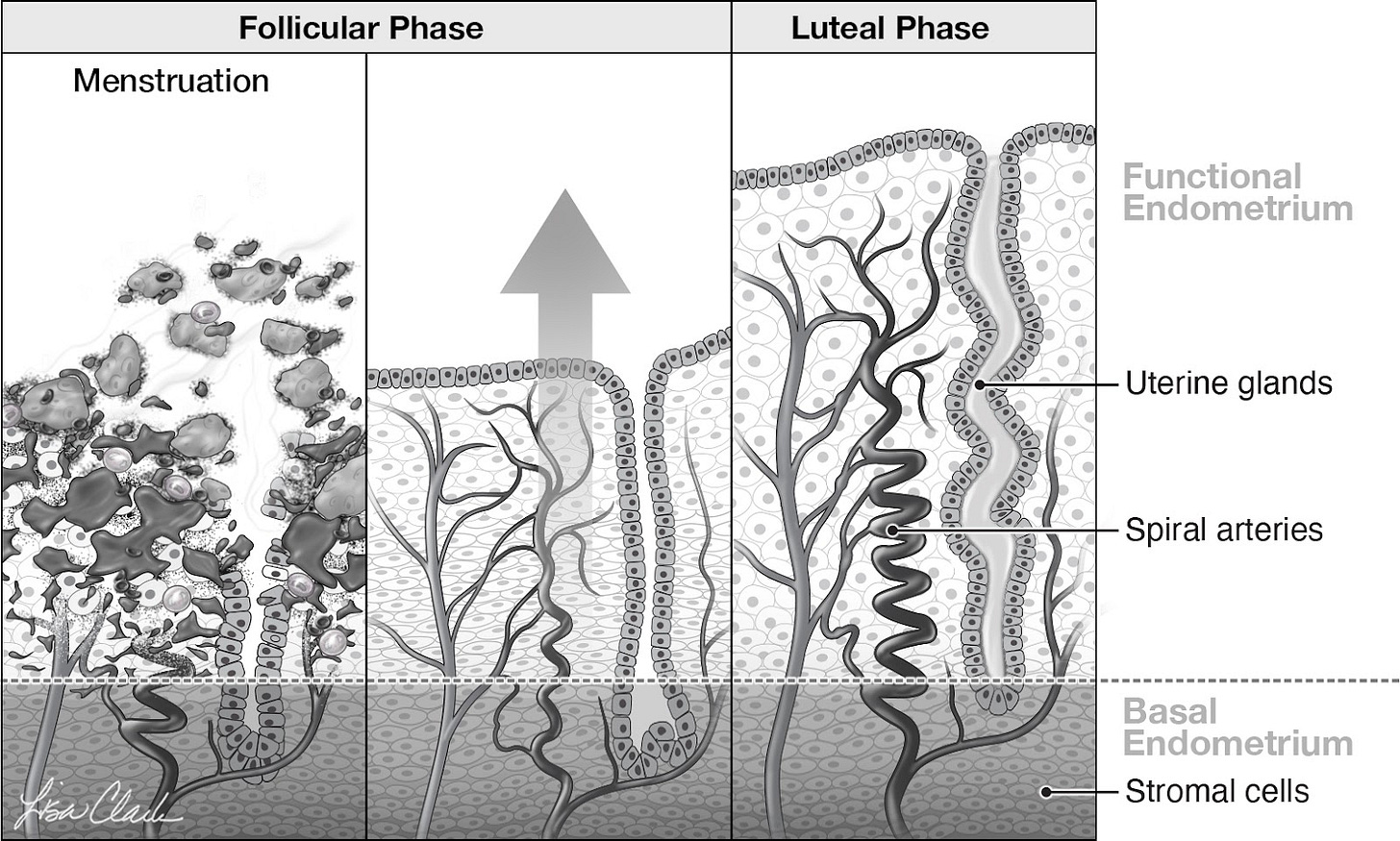

Let’s start with a very quick and pared-down tour of the menstrual cycle. During the follicular phase (the first part of the cycle), estrogen causes the endometrium (uterine lining) to thicken, and tiny arteries and veins grow into this thickened lining (see the middle panel of the image below). When ovulation occurs, the leftover sac of tissue in the ovary becomes the corpus luteum, which is a progesterone-producing machine. Progesterone causes the cells in the endometrium (uterine lining) to undergo changes to prepare for the implantation of a fertilized egg. The part of the cycle from ovulation to the start of the first day of bleeding of the next menstruation is called the luteal phase (panel 3 below). If the corpus luteum doesn’t receive a signal indicating that implantation has occurred, it stops producing progesterone, and it is this withdrawal of progesterone that triggers a chemical cascade that causes the blood vessels that supply the uterine lining to spasm and also results in the production of inflammatory chemicals. The blood vessels break open, and blood pools between the top and bottom layers of the uterine lining. The physical presence of the blood and the inflammation causes the top layer of the uterine lining to separate (see panel 1 below). There are also chemicals that limit clotting to help the blood flow out.

(This beautiful illustration is from my book Blood: The Science, Medicine, and Mythology of Menstruation).

The fluid that leaves the uterus is blood from the ruptured blood vessels, the dislodged uterine lining or top layers of the endometrium, any mucus from the uterine lining, and inflammatory fluid. (At this point, I have a vision of a pipe that was buried in the backyard that has burst and created a mini river of soil as well as leaves and twigs that are along for the ride). As the menstrual fluid passes through the cervix and vagina, it picks up cervical mucus and vaginal discharge. When the menstrual fluid makes it into a menstrual product it’s about 50% blood and 50% endometrium/mucous/inflammatory fluid/discharge. The blood part is the same as blood drawn from your arm; it’s not special blood. The mix of blood to inflammatory fluid can vary for various reasons, but we’ll stick to 50/50 for ease of discussion.

To recap, there isn’t blood hanging out in the uterus waiting for menstruation; the blood comes from what is essentially an injury to the lining of the uterus. And here’s a fun fact: menstruation is the only scarless healing process in the human body! Shedding is a term that is often used in descriptions of menstruation, but it refers to only the uterine lining, as in the “endometrium is shed.” It shouldn’t be used in a way that makes people think it’s only the endometrium or uterine lining that is coming out in menstrual fluid.

How Much Blood is There?

The amount of blood, meaning what is coming out of the blood vessels, depends on how quickly the flow is stopped, which is controlled by many factors, such as the blood’s ability to clot, the amount of prostaglandins and the inflammatory chemicals produced by the endometrium (uterine lining), and the hormones coming from the next cycle, as the estrogen produced by the next developing follicle helps to repair the uterine lining that is left behind.

The upper limit of normal for menstrual blood per cycle is 80 ml (2.7 ounces), and this was traditionally calculated with a rather complex method that can tell the amount of hemoglobin in the fluid on a pad or a tampon. However, as mentioned earlier, blood is only about half of menstrual fluid, so up to 160 ml (5.4 ounces) of fluid a cycle is within the normal range. It’s not as if we can look at what’s in a menstrual cup and eyeball the blend like admiring the color of a fine wine. “That there is 62% blood; I tell you it was a good month.” Knowing how much menstrual fluid is blood matters in some studies, but from a practical standpoint, it’s the whole shebang that matters. Since collecting menstrual fluid would be cumbersome, we have some more practical ways to tell us if menstruation (meaning menstrual fluid) is excessive:

Changing pads/tampons more than every 1-2 hours

Soaking onto clothes or sheets despite using a menstrual product

Clots > 2 cm (0.7 inches)

Sensation of gushing

Needing to double up on menstrual products (for example, you must wear a tampon and a pad)

Also, if you feel your menstruation is heavy, then it warrants a discussion.

With what we call an ovulatory cycle (meaning there is ovulation), people can have heavy periods because they have more bleeding from the blood vessels, they have more inflammatory fluid, or both (side note: heavy bleeding when ovulation hasn’t happened or is irregular is a different discussion). An increase in blood loss can happen when the blood flow isn’t stopped. For example, when someone has a bleeding disorder, the blood's ability to clot is compromised, so there is more blood loss. The uterine lining (endometrium) produces hormones called prostaglandins, which dilate the blood vessels and promote bleeding. Evidence shows that some people with heavier periods may produce more prostaglandins in their endometrium. There are gynecological conditions that can contribute to heavy periods, such as endometriosis and fibroids (benign tumors of the uterine muscle).

How Do NSAIDs, Drugs like Ibuprofen, Reduce Menstrual Fluid Loss?

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDs decrease the production of prostaglandins in the endometrium, so the blood vessels can constrict more, reducing blood loss. They may also reduce the inflammatory fluid, but they don't result in the uterine lining being left behind. On average, NSAIDs reduce menstrual fluid loss by about 25-35% (some studies calculate actual blood loss and others look at menstrual fluid volume).

The three NSAIDs that have been studied to reduce menstruation are ibuprofen, naproxen, and mefenamic acid. The doses of ibuprofen and naproxen needed to reduce menstruation are prescription doses, not over-the-counter doses. Typically, the medication is started with the first sign of bleeding, but it may work even better when started a day before. Usually, the medication is taken for 2-3 days (until the flow is minimal). Doses and regimens that are used include:

Ibuprofen 600 mg 2-4 times a day or 800 mg 3 times a day

Naproxen 500 mg twice a day for the first day, then 250-500 mg twice a day

Mefenamic acid 500 mg three times a day or 500 mg then 250 mg four times a day (this is prescription in the United States)

Not everyone can take NSAIDs, for example, if you have a bleeding disorder or have had a gastric bypass. The advantage of NSAIDs is that you are only taking them for a few days a month, they are generally affordable, and most people find a 25-25% reduction in menstrual fluid a positive change in quality of life. They don’t work for everyone; for example, if you have fibroids, they may not help, and some people seem to be menstrually resistant to NSAIDs, for lack of a better expression. However, as this isn’t something you have to try for months to see if it will help, trying it for one or two cycles might be an option to discuss with your healthcare provider.

Can You Stop Your Periods With the TikTok Ibuprofen and Jello Hack?

There are two versions going around. One is ibuprofen and gelatin; the other is ibuprofen, Jello, and lemon juice (maybe Big Jello wanted in on the menstrual action?). And the claims range from delaying your period to stopping it from coming altogether. Sometimes, I wonder if people looking to make viral content randomly pick shit from around their house and then, with inappropriate confidence, make bold proclamations about body functions they have drawn from a hat, like some bizarre medical version of the board game Clue.

There are several studies that have evaluated NSAIDs for reducing menstrual flow. If NSAIDs completely stopped periods, I wouldn’t be quoting you just a 25-35% reduction in menstrual flow from these actual studies. Look, if ibuprofen reliably stopped a period, everyone would know because we prescribe it a lot for menstrual cramps. We also tell people to start the day before their period if possible. But many people who menstruate also people take NSAIDs for nonmenstrual reasons, and they would be making appointments to discuss the fact that their periods have now stopped. Might there be one or two super responders with NSAIDs? Of course, there are always outliers.

What about the claim that NSAIDs in high doses can delay the onset of a period by 1-2 days? Prostaglandins are intimately involved in menstruation, so it’s a valid hypothesis, but no quality clinical trials support this assertion. Remember, the menstrual cycle normally varies in length by up to 7 days cycle-to-cycle. The kind of study needed to prove that NSAIDs could delay periods by 1-2 days would take hundreds, if not thousands, of participants where the patients tracked their cycles for several months before taking the medication and then followed for one or more cycles after taking NSAIDs. These were the kinds of studies that were used to tell us the impact of the COVID-19 vaccine on the menstrual cycle, and we do not have those studies for NSAIDs.

Researchers have looked to see whether or not NSAIDs delayed ovulation, which could delay the next period. In one study, women took ibuprofen 800 mg three times a day for 10 days starting shortly before ovulation was expected. The ibuprofen had no effect on ovulation, and no delays in the next menstrual cycle were reported. While this was a small study, other studies also show no consistent effect on ovulation or the onset of the next cycle. The only study that I can find that supports the idea that NSAIDs can delay the next menstrual cycle is from 1983, involving 12 patients. The journal is no longer in print, and I can’t get the article, so I have no idea when in the cycle the medications were given, the doses, and how many cycles were observed. The abstract tells me nothing, and the more recent studies looking at the impact of NSAIDs are almost certainly better. This means that if you want to delay your next period, NSAIDs are not the way to go, although it is possible that some people have such a significant reduction in flow with NSAIDs that it is mistaken as a delay in the onset of menstruation.

If you do want to delay a period, hormones are your best bet, and your healthcare provider can prescribe them.

Final Thoughts

You don’t have to refer to your menstruation as menstrual fluid! You can, of course, call it whatever you want. My favorite euphemism is there are communists in the funhouse. I refer to menstruation as blood because that is what most people are used to, and it is blood, just mixed with some other stuff.

And if you want a really deep dive like this into all aspects of the menstrual cycle, I have a book for that!

As always, the information here is not direct medical advice. If you have questions, leave them below. I try to reply to the easier ones directly in the comments (obviously, again, not individual medical advice). For those questions that are more complex, I tuck them away and try to incorporate them in future posts.

References

Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Sep 19;9(9):CD000400. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000400.pub4.

Yang H, Zhou B, Prinz M, Siegel D. Proteomic analysis of menstrual blood. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012 Oct;11(10):1024-35. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.018390. Epub 2012 Jul 20. PMID: 22822186

Fraser IS, McCarron G, Markham R, Resta T. Blood and total fluid content of menstrual discharge. Obstet Gynecol. 1985 Feb;65(2):194-8. PMID: 3969232

Levin RJ, Wagner G. Absorption of menstrual discharge by tampons inserted during menstruation: quantitative assessment of blood and total fluid content. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986 Jul;93(7):765-72.

Manuel B. Donoso, Ramón Serra, Gregory E. Rice, María Teresa Gana, Carolina Rojas, Maroun Khoury, José Antonio Arraztoa, Lara J. Monteiro, Stephanie Acuña, Sebastián E. Illanes; Normality Ranges of Menstrual Fluid Volume During Reproductive Life Using Direct Quantification of Menses with Vaginal Cups. Gynecol Obstet Invest 12 July 2019; 84 (4): 390–395

Smith SK, Abel MH, Kelly RW, Baird DT. Prostaglandin synthesis in the endometrium of women with ovular dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981 Apr;88(4):434-42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1981.tb01009.x

Uhler ML, Hsu JW, Fisher SG, Zinaman MJ. The effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on ovulation: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Fertil Steril 2001; 76:957-961.

Athanasiou S, Bourne T.H, Khalid A, Okokon E.V, Crayford T, Hagstrom H.G. Effects of indomethacin on follicular structure, vascularity, and function of the periovulatory period in women. Fertil Steril. 1996; 65: 556-560

I love, not only the educational piece of this, but also the bits of humor and overall writing style. It's not easy to make it fun to read about menstruation, but here we are.

I really want you to just read this blog post while drinking. And other blog posts. And then get other healthcare providers on board. Like Drunk History, but for medical professionals.

Jello & lemon juice! As the saying goes, when you think you've heard it all, you haven't...